North Carolina

BY EMILY GRIFFIN, NORTHEASTERN GUEST STUDENT

Nice big, boat ramps in North Carolina!

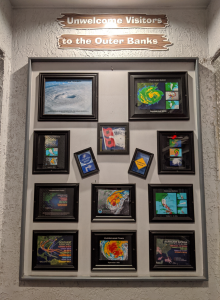

On February 18, 2020, the Coast Systems Lab drove down to North Carolina to get sediment cores and find out more information about hurricanes that have occurred there in the past. The team included myself (Emily Griffin, a Guest Student), Ethan St. Aubin (another Guest Student), Mitchell Starr and Nicole d’Entremont. This was about a 16-hour drive which included a lot of podcasts, gas stations, and snacks. This was going to be my first time coring, so I was not sure what to expect other than that we were going to get covered in mud. We were towing our pontoon boat, which we had strapped about thirty 9-meter long aluminum and plastic barrels, along with all of the other coring equipment.

Once we got to our first destination in the Emerald Isle, NC, we checked the forecast and to our unfortunate surprise, the weather had changed from 70 degrees and sunny to 35 degrees with rain and wind. Nevertheless, we still planned on coring. We drove to the first site in the morning and the wind was so strong that the water was crashing over the sides of the dock. There was no way that our boat was going to be able to handle these conditions.

Coring at Alligator River

The same was true the next morning. There was even snowfall, which almost never happens in NC. Most of the local schools were closed. We were really beginning to think we brought the New England weather. At least we got to meet some nice local people who gave us insights about how deep the water was in different areas.

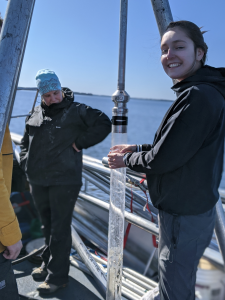

The third day we were finally able to go out coring! Since the areas that we were going to were relatively shallow (about 1.5-2 meters deep), we used the rod-driven system which entails a vibrating head that is powered by a motor and attaches to the top of the aluminum barrel in order to vibrate it into the ground. Then, while the barrel is being driven underwater, we attach rods onto the top and guide it down in order to collect as much med as possible.

Emily and Andrea are ready to core, even with freezing temps!

We also attached a piston to the bottom of the barrel that will slide up as the barrel gets filled with mud in order to make sure the mud does not fall out while we are pulling it back up. This process is very intense as the vibrating head vibrates the entire barrel so much that it is hard to hold onto. Nicole still laughs at the look on mine and Ethan’s face after we pulled up our first core. This is an all hands-on procedure because as the core gets pulled up, it has to be capped really fast or else the mud might be lost and then we would have to do it all over again. Everyone has a role and we all have to communicate with one another in order to make sure we do not lose any mud. As someone who is never done any sort of fieldwork like this before, it was very interesting to see how much effort goes into getting the samples that we work within the lab. Not to mention, we were on a time crunch as the tide was going out and we were not going to be able to go back to the dock in such shallow water.

All of the sites that we went to during this trip had very shallow water and therefore brought many challenges for coring. Because of this, we were also not able to get very long cores. However, we still managed to get mud from every site we went to.

The next day we went coring at Camp Lejeune, a military base on the Emerald Isle. Other than having to dodge many oyster traps, bridges, and the sound of a fighter jet having landing practice right next to us, we were able to successfully core. Ethan and I started to pick up on the procedure- what to start preparing, what to have ready in your hand, etc. We even saw some young dolphins!

The last day we drove up to the northern part of the Outer Banks. We went to a large river off the coast called Alligator River. It was a two-hour boat ride to the location. The water was a bit deeper here (about 4 meters) so we were able to get some longer cores. Everything was going really well at this site until the come-along (the machine we use to pull up the core) broke. We tried fixing it for a while but nothing was working. Luckily, Nicole was able to figure out a way to tie some knots to attach the other come-along to in order to pull up the core.

It’s as if they knew we were visiting….

This was extremely difficult as it was stuck in a thick layer of clay. We have to pull up this core inch by inch. Luckily, the clay was so thick at the bottom that we didn’t lose any mud, and we were able to get about a 5-meter core, despite the come-along breaking. At this time clouds were rolling in so we had to leave the site before it started down pouring.

The weather really did not work out for us on this trip. It was unfortunate that we weren’t able to do more coring, but I was still able to get a good idea of the rod-driven process. Once we got back to the lab and split open the cores, it was fascinating to see the different layers in the mud and know that this mud will be able to give us insights into thousand-year-old storms. My lab work has now made much more sense with this new background-knowledge of how these cores are collected. Overall, the trip was fascinating and I was able to learn so much about field-research. I definitely have a new level of respect for scientists after seeing the lengths they go to in order to get their data.