Bears, Bingo, and Bat-cows

This post was written by Ph.D. Candidate Hanny Rivera

A softly illuminated castle stood overlooking the snow-blanketed streets of Cesky Krumlov, a medieval village tucked away in southern Czech Republic. I walked slowly towards the town square dragging my luggage over the rugged cobblestone streets, conversing with a fellow scientist also here for an intensive workshop to learn, and with some luck, begin to master the ever increasing suite of tools and programs used by biologists to explore the genetic variation that shapes the world around us.

Molecular biology has come a long way since the mid 20th century when Rosalin Franklin, James Watson, and Francis Crick unraveled the structure of DNA. Today, DNA sequencing machines produce hundreds of millions of sequences. The questions and processes that you can ask using modern technologies seems endless and ever expanding as techniques become more and more sophisticated. From comparing DNA sequences between organisms in order to understand the evolutionary relationships between species, to exploring how an organism responds to different conditions by expressing different proteins. Scientists are only beginning to uncover a wealth of information from the DNA sequence itself as well as how that basic blueprint is interpreted and used.

So how does one begin to learn about all the different tools, techniques, and computer programs today? Mainly, with patience and secondly, with lots of coffee. The Workshop on Genomics was organized over two weeks with lectures and hands-on computer lab assignments running from 9 am to 10 pm, 6 days a week (hence the caffeine requirements). About 80 of us, graduate students, postdocs, and even a few PIs would arrive at Cesky Krumlov’s town theatre in the morning, soak in all the knowledge of that day’s lecture along with its well-planned coffee breaks.

In the afternoon and evening, we would line up along long tables in the House of Prelate with our laptops plugged into bundles of Ethernet cables that juxtaposed the centuries-old frescos and chandeliers of the government hall. Together we would work through that session’s assignment whether is was genome assemblies or RAD-seq analyses. The typical frustrations of coding and computing all applied, from Amazon’s cluster locking us all out because it thought we were trying to hack in by simultaneously creating 80 virtual machines at once, to staring blankly at that line of code that keeps stalling despite being perfectly crafted… no, wait, there’s only a single dash instead of two before that option, argh.

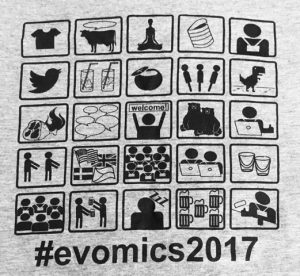

In an attempt to ensure we didn’t spend all of our time correcting forward slashes and double dashes, the organizers created a bingo game with must-do Cesky Krumlov experiences. It ended up artistically depicted in our workshop t-shirt {insert pic}. One of these activities was to see the bears. The castle of Cesky Krumlov has been home to bears since the early 18th century when they were acquired as a display of diplomacy between the inhabiting Rosenberg family and the Orsini family in Italy (‘orsino’ means bear in Italian). Sadly, I failed to see the bears during my time there, though given the frigid temperatures and a bear’s propensity to hibernate I can’t say I’m surprised, even if disappointed.

With the vast number of different bioinformatics programs available, making sure that your data make sense from a fundamental, biological point of view is crucial to avoid over or misinterpreting your results. Prof. Chris Wheat’s closing lecture for the workshop enticingly titled “Lies, damn lies, and genomics,” was a cautionary tale of what happens when one is too trusting of methods and forgets some of the more basic principles of biology. He humoredly highlighted studies in which this was the case. For instance, one study tried to find evidence for convergent evolution of echolocation in mammals, expecting to find more similar changes co-occurring in the genome of dolphins and bats (both echolocators) than other species. While the authors did find some evidence for such similarities, their analysis was based on an evolutionary model that was not accurate for studying convergent evolution. When their data were analyzed using the correct null model, it showed instead that bats and cows appear more similar. Wheat’s main argument was that at the end of the day, we should rely most on our fundamental biological training and utilize all the new-fangled and fancy gadgets of bioinformatics as biologists.

While I don’t expect to find any evidence of bat-cows in my own research, I am thoroughly looking forward to applying many of the techniques, tools, and ways of thinking that I learned during this workshop to studies on the population genomics of corals in the central and western Pacific Ocean. With some hard work (and likely lots of more coffee) I hope to find hints of what makes corals in particular reefs able to withstand much hotter temperatures than its neighbors. Stay tuned for those results, coming (fingers crossed) soon.