How sea butterflies weather the seasons

I’m posting to highlight our recent publication: Maas AE, Lawson G, Wang ZA, Bergan A, Tarrant AM (2020). Seasonal variation in physiology and shell condition of the pteropod Limacina retroversa in the Gulf of Maine relative to life cycle and carbonate chemistry. Progress in Oceanography 186: 102371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2020.102371 (*If you don’t have access and want a copy, please email me: atarrant at whoi dot edu). The review process was slow this time around, so we are very happy to have the paper out!

We asked how the population structure and health condition of Limacina retroversa (“Limacina” for short) vary over the seasons. Pteropods like Limacina are small gastropods (“cousins” of snails and nudibranchs) that are sometimes called “sea butterflies” because they use wing-like muscles to swim through the water. Many pteropods, including Limacina make delicate shells out of calcium carbonate. Many studies, including work by our group have shown that ocean acidification can challenge the ability of pteropods and other animals to make these shells.

Ocean acidification is the ongoing decline in pH within the oceans caused by excess carbon dioxide uptake from the atmosphere due mainly to anthropogenic burning of fossil fuels. But on top of this overall trend, the acidity and other chemical characteristics of the seawater change over the course of the year for a variety of reasons. For example:

- Temperature – during winter, the cold water can hold more carbon dioxide than warm summer water. Seasonally warm water can be thought of as an open soda can going “flat” on a warm day.

- Productivity: as phytoplankton begin to grow in the spring, they remove carbon dioxide to use for photosynthesis. This decreases the acidity.

Anthropogenic ocean acidification is laid on top of this natural seasonal cycle. In addition, seasonal changes in other aspects of the environment, such as temperature and food availability may affect the ability of pteropods and other animals to cope with acidification. When pteropods are well-fed and at a comfortable temperature, a little acidification may not be such a big deal, but when the are already feeling hungry and stressed, it might be another story.

What we did we learn about Limacina populations?

Maas et al 2020.

We sampled Limacina from the Gulf of Maine across the seasons using MOCNESS tows to look at how populations change over the year. The MOCNESS is a special set of nets that allows us to sample plankton from “layers” of water at different depths.

A very exciting aspect of this work was that the last person to really use a time series to study Limacina populations in the Gulf of Maine was Alfred Redfield.

Yeah that’s right, the namesake of:

- a famous oceanographic ratio,

- the building in which I work

- our departmental softball team.

Yes, that Redfield. For me this is every bit as cool as getting to use Holger Jannasch’s Winogradsky columns. But I digress. Redfield found that the animals were present throughout the year but patchy with a main reproductive season in Spring.

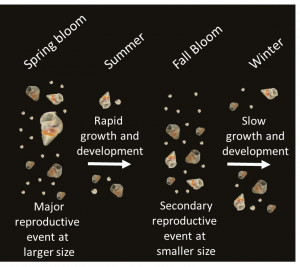

Like Redfield (wow, it feels cool to say that), we observed patchy distributions…which can be really annoying when you are trying to sample enough animals to study each time. In general the animals were found in very shallow water (>50m), where phytoplankton were abundant. Pteropods, including large reproductive individuals and lots of small juvenile pteropods, were usually abundant during the spring bloom and summer….but (darn that patchiness) not always! We also saw a second smaller peak in small juveniles in the fall. This suggests that the main reproductive event was in the spring, but reproduction also continues through the summer and a second generation might even grow to maturity during summer to produce the fall cohort. In addition to this, we are likely seeing waves of pteropods carried into our sampling site from offshore. Teasing these factors apart is not easy, and we are still thinking about how best to do it.

Spawning in the spring makes particular sense biologically. There is a lot of food around due to algal blooms, and high rates of photosynthesis reduce the acidity of the water.

What did we learn about Limacina physiology across the seasons?

In many ways winter may be the hardest season for Limacina in the Gulf of Maine. There isn’t a lot of food around, and the water is at its most acidic.

Animals collected in January had the worst shell condition (damaged shells are more opaque) and we saw changes in gene expression that were similar to those that we observe after exposing Limacina to acidified water in lab experiments. During the fall, our gene expression measurements suggest that animals are storing lipids in preparation for overwintering. We predict that in the future, impacts of further acidification on Limacina in the Gulf of Maine will first be noticed during the fall reproductive events.

What’s next for us?

We’ve already completed a large series of experiments in which Limacina were collected each season and exposed to ocean acidification in the lab. The goal of these studies was to understand how the seasonal variability in pteropod condition (as I describe above) affects their ability to respond to an added stressor. We can test our prediction that the fall and winter populations might be most vulnerable. This will help us to better understand how this species might respond to future conditions.

P.S.

This work was sponsored by the United States National Science Foundation. Federal support of scientific research is critical to our ability to understand how our world continues to change.