Krill on alert

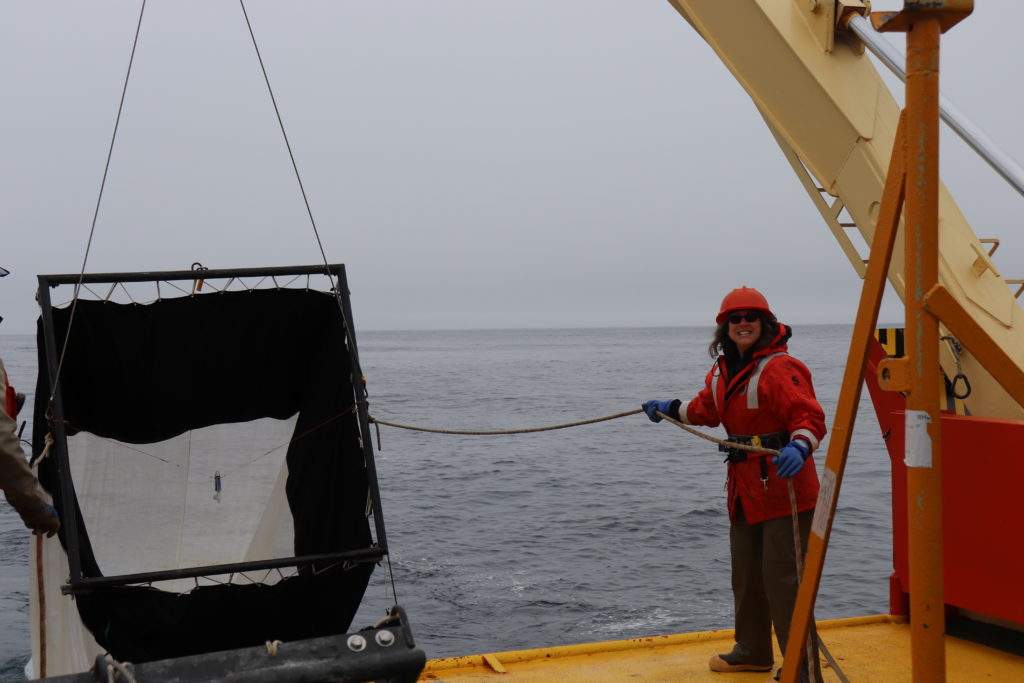

January 23, 2019 (Note: this is #22 in a series of posts describing my NSF-sponsored fieldwork in Antarctica aboard the Laurence M. Gould). The photo above of Debbie Steinberg deploying a plankton net was taken by Patricia Thibodeau.

We’re working away like busy little bees here on the ship, trusting that our day-to-day efforts will ultimately be synthesized to provide insight into the bigger picture of the workings of the Antarctic ecosystem. Sometimes insight comes in flashes (a “eureka” moment) and sometimes it’s an image that slowly forms layer by layer. As an example of the latter, a major new study was released this week in Nature Climate Change showing that Antarctic krill distributions have shrunk nearly 300 miles southward in association with warming of the oceans (links to the publication and VIMS press release). This matters because krill are a big part of the biomass (living material) in this polar ecosystem. They are an important source of food for penguins and whales and seals (and sometimes people). Changes in krill populations affect how energy moves through the food web and eventually how carbon dioxide that’s captured via photosynthesis can sink out and be buried in the deep sea. The study used data from zooplankton net tows conducted between 1926 and 2016, including net tows conducted within the Palmer LTER project.

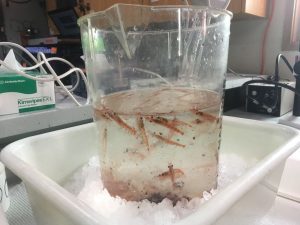

Krill awaiting sorting and measuring in the ship’s wet lab.

Our Chief Scientist, Debbie Steinberg is a co-author on the manuscript. Over the past few weeks, I’ve been watching her tirelessly leading the zooplankton sampling effort while also managing the overall cruise plan to adjust to local ice conditions and accommodate the needs of the diverse scientific teams. I’ve been particularly impressed by her attention to detail. With each net tow, the plankton are sorted into species. Krill and salps are individually measured and observed for reproductive condition. Other groups are counted, and their bulk volume carefully recorded. The sorted samples are preserved for later studies back in the lab. If it were up to me – and thank goodness it’s not – I think the operation would probably have been a lot sloppier. What’s the difference if a few krill stick to the sides of the bucket and don’t get counted? Who cares if an Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) accidentally gets mixed in with a Thysanoessa macrura? It matters if you are trying to detect changes over time and space. The recent paper shows that the northern populations of Antarctic krill have been declining. But that’s just only the short version of the story. The sorts of precise careful measurements Debbie’s group has been making over the years provides fine-scale, high-quality data that can be used to more finely predict how the ecosystems responds to year-to-year changes and smaller scale environmental gradients. It’s a reminder that the details matter.