Data Visualization

Welcome to our webpage presenting preliminary results from our recent Distributed Sensor Network (DSN) deployment in the Gulf of Mexico from July 23 – July 27, 2024.

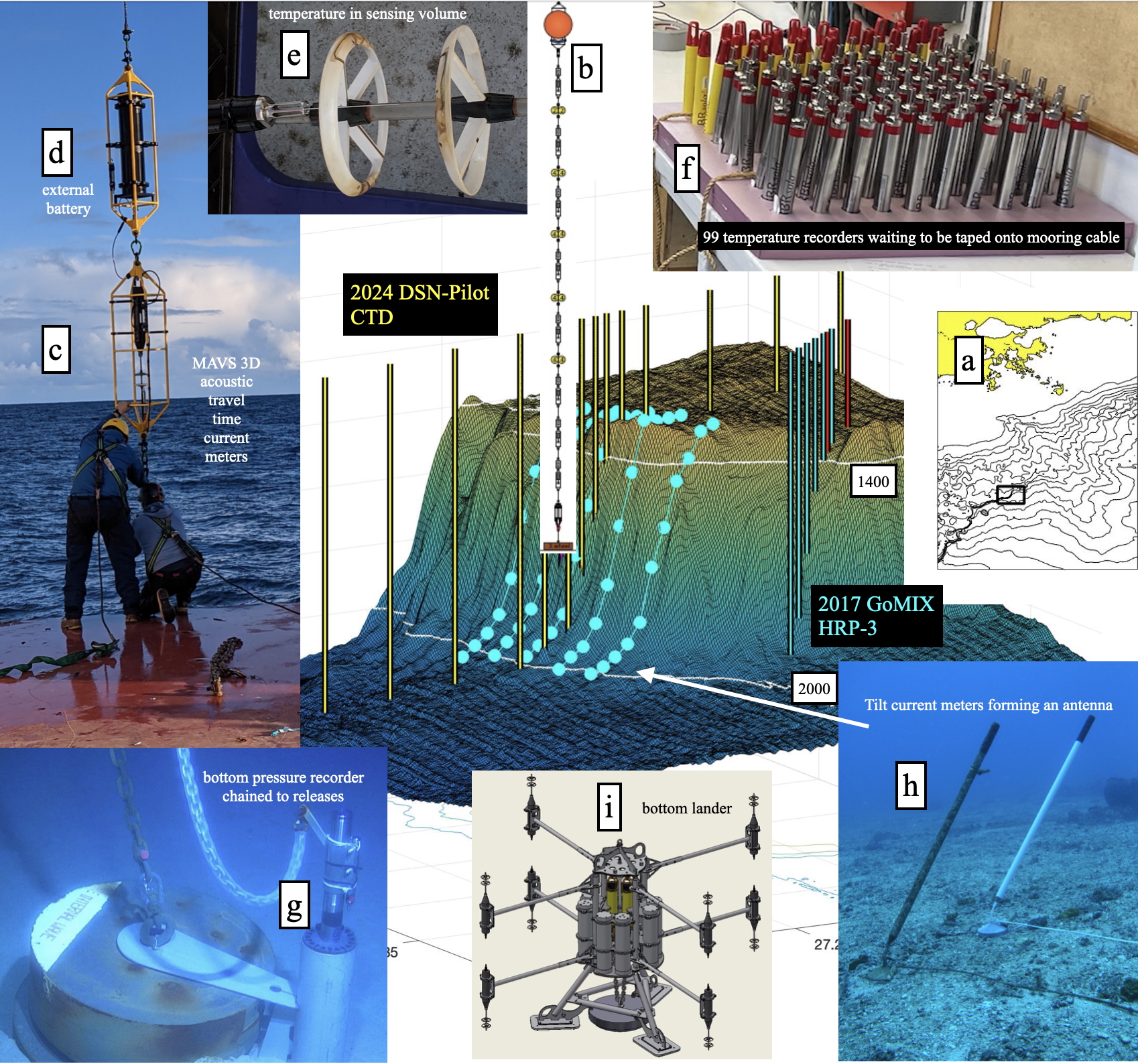

Distributed Sensor Network, instrumentation, and location

Figure 1: Distributed Sensor Network assets draped over a steep escarpment in the Gulf of Mexico (a). The sensor network is arranged about one or more conventional taut wire moorings (b) hosting MAVS acoustic travel time current meters (c) that provide estimates of 3D currents, turbulent dissipation through inertial subrange formulas, and fluxes of momentum and buoyancy at time scales of seconds to hours. A single external battery pack (d) enables 6 months of sampling at 5 Hz. A serial streaming temperature recorder with custom 10 cm long string whose tip is placed within the sensing volume of the acoustic current meter (e) provides co-located temperature/velocity measurements. Fifty to one hundred self-contained temperature recorders (f) sampling at 0.5-1.0 Hz for 1 year duration are taped onto the mooring and provide high vertical resolution of internal wave and outer turbulent boundary layers. Direct estimates of energy flux (pressure work) can be obtained by using the temperature recorder data to vertically integrate the hydrostatic relation and placing a bottom pressure recorder in a special frame on the anchor (g) to provide time varying pressure as a function of height above bottom and then combining these with the 3D currents. Individual Tilt Current Meters (TCMs; h) are self-contained units and sample at 8 Hz with a duration of one-year. In the Sensor Network, these units are deployed along lines of 6-10 km length with anchors at either end, but the nominal extent is virtually unlimited. A bottom lander (i) populated by 8 MAVS current meters measuring at 0.5 and 2.5 m height above bottom provides high vertical resolution of the turbulent OBBL, directly quantifying the frictional stress. As described, the Sensor Network is a base that can be complimented by more traditional sensors. In total, the Sensor Network assets return full resolution of turbulent and internal waveband contributions to budgets of momentum, buoyancy, vorticity and energy.

Days -2 to 0

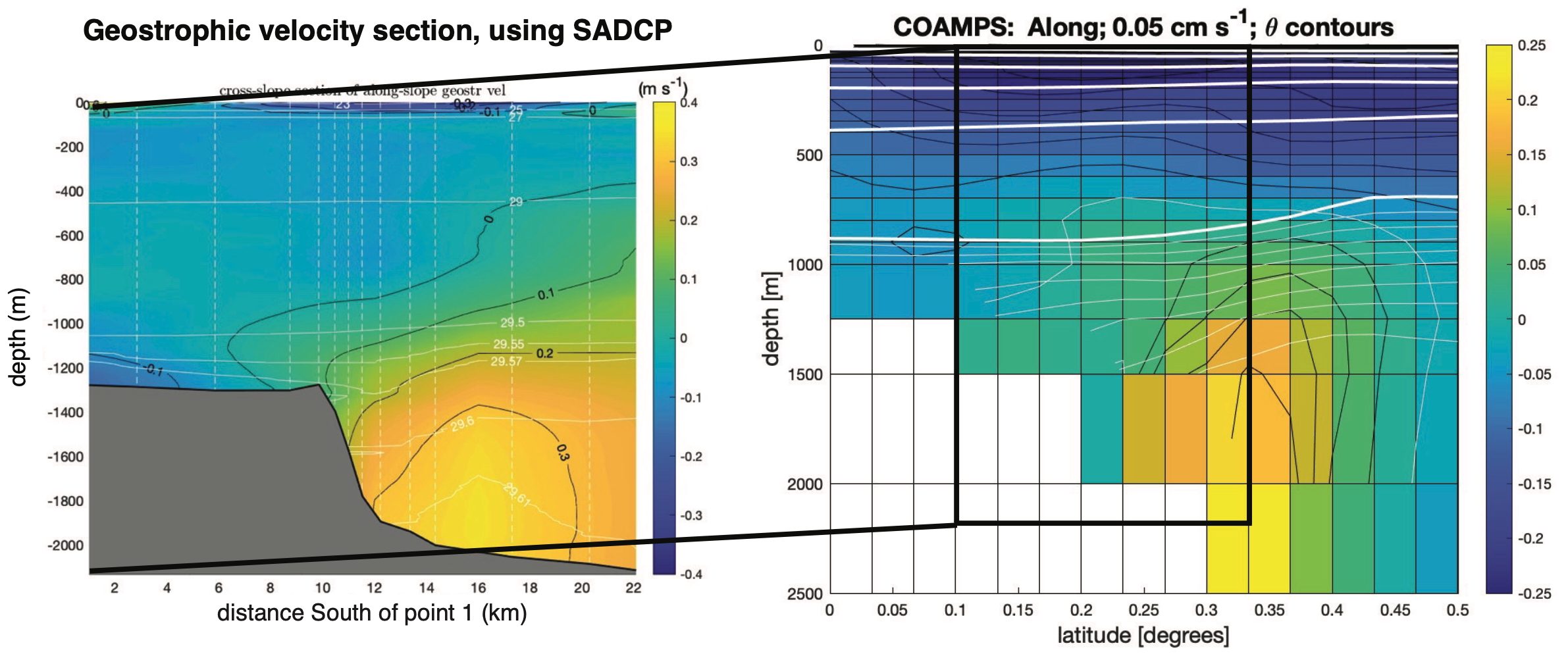

- When we arrive onsite, strong flow from west to east is noted at the base of the escarpment

Figure 2: DSN-Pilot. Left hand panel: Section of geostrophic velocity from shipboard CTD measurements obtained during the 3-day DSN deployment, prior to DSN data in Figures 4-7. See yellow/black vertical lines in Figure 1. Right hand panel: the corresponding 3-day time mean section from the COAMPS model. The tiling represents the vertical and horizontal grid of the 2 nautical mile model output.

DSN-Pilot. Left hand panel: demeaned SADCP E-W velocity over the 3-day DSN-Pilot deployment. Right hand panels: demeaned COAMPS model velocity. Note the upward phase propagation of the near-inertial signal in the data. The observed vertical phase propagation is confined to the upper 150 m in the o observations. The model exhibits a considerably different vertical structure. Model-data discrepancies can result from the vertical structure imposed by the model’s data assimilation scheme (Gregg Jacobs, personal communication 2024). Why is this important? The vertical projection at the bottom boundary serves as external forcing for the OBBL. See Figure 4 for the response at inertial frequencies.

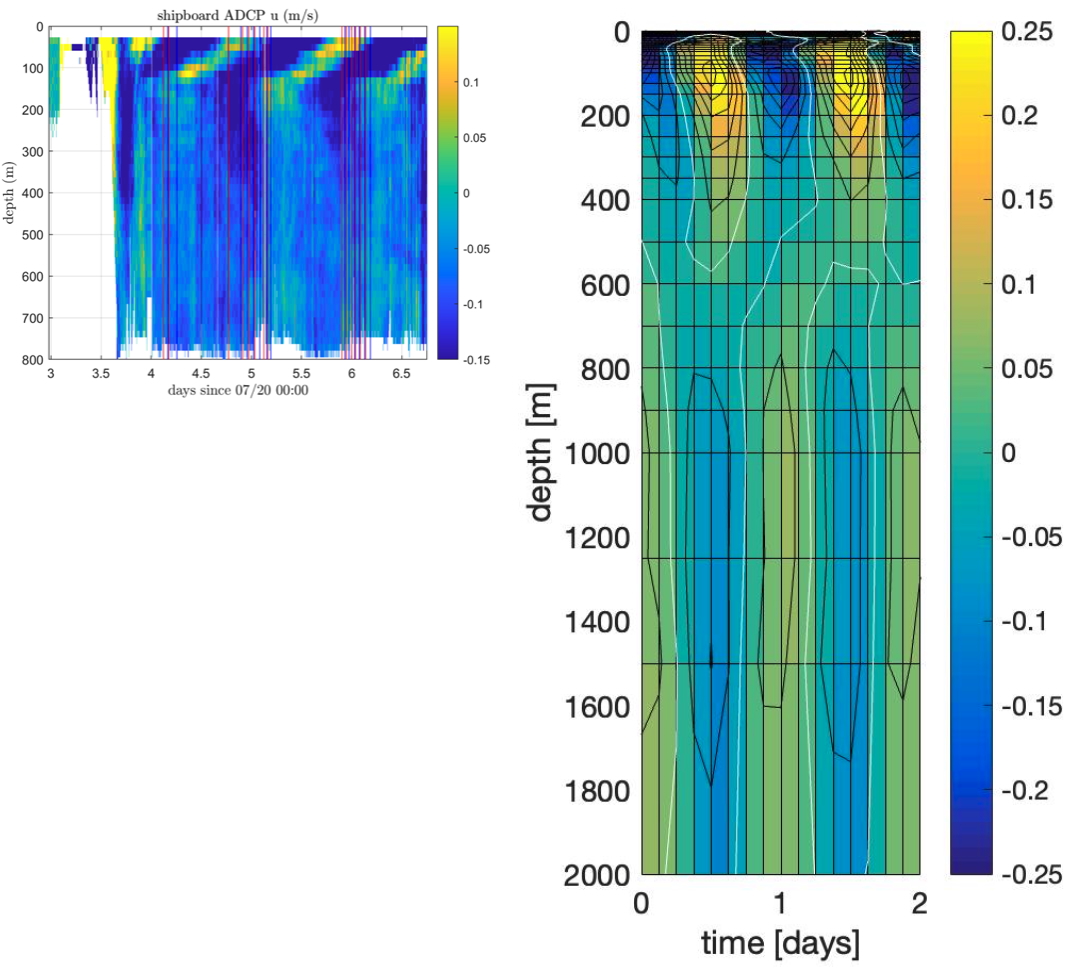

Days 0 to 2

- When we arrive onsite, strong flow from west to east is noted at the base of the escarpment

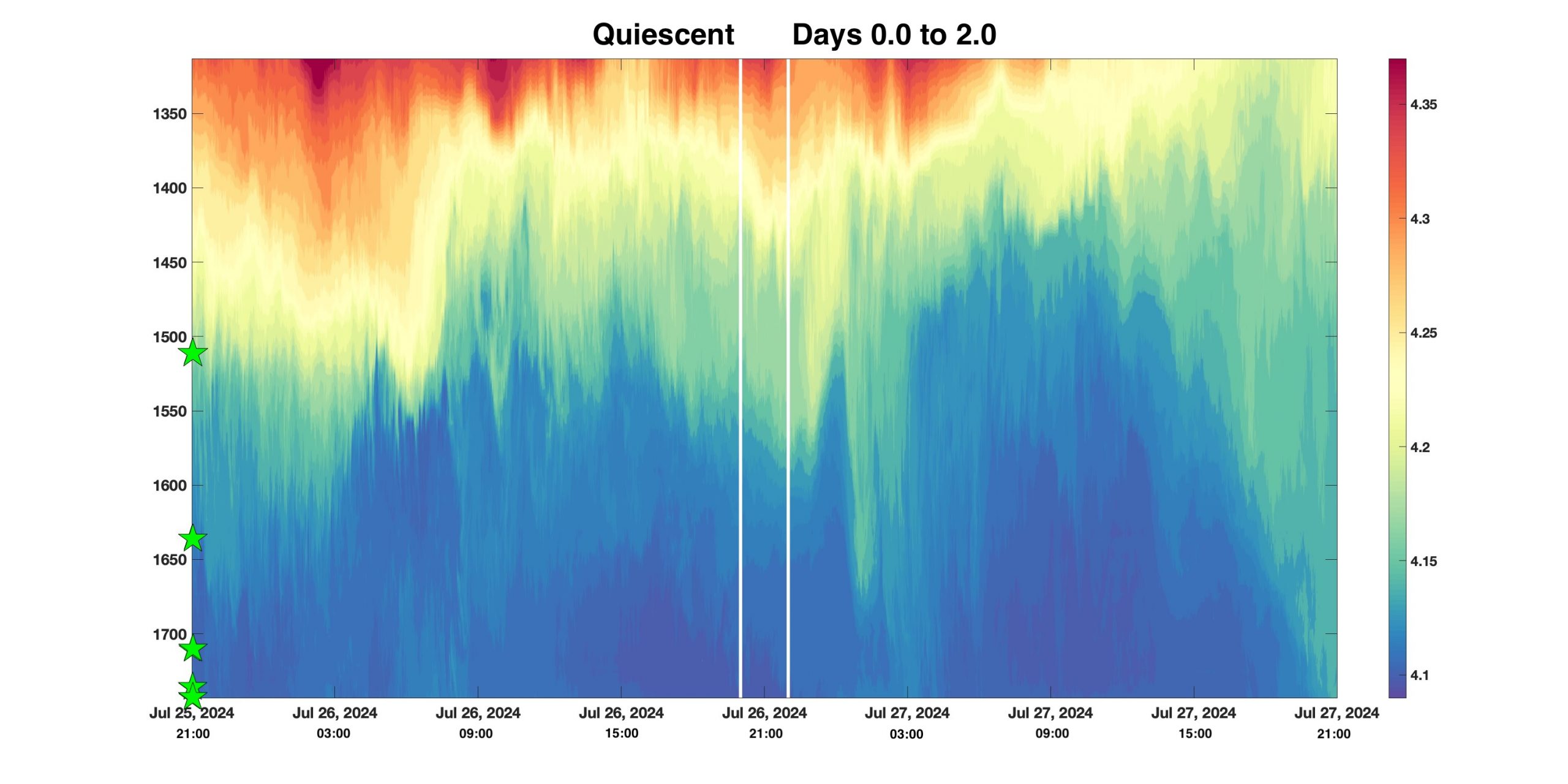

Figure 4: DSN-Pilot. Time series of temperature recorder data for the first two days of the mooring deployment. The 0.2-0.3 m s-1 eastward velocity on the slope during deployment (Figure 2) has evolved to a more ’Quiescent’ state, Figure 5. Note the heaving of isotherms having inertial periodicity and the appearance of temperature inversions implying static instability. Sampling rate is 1 Hz and there are 68 sensors in the bottom 400 m of the 900 m tall mooring. The bottom most sensor is mounted on the acoustic releases, 3 m above bottom. Green pentagrams depict the locations of MAVS current meters. The white lines delimit the duration of time averages presented in Figure 5.

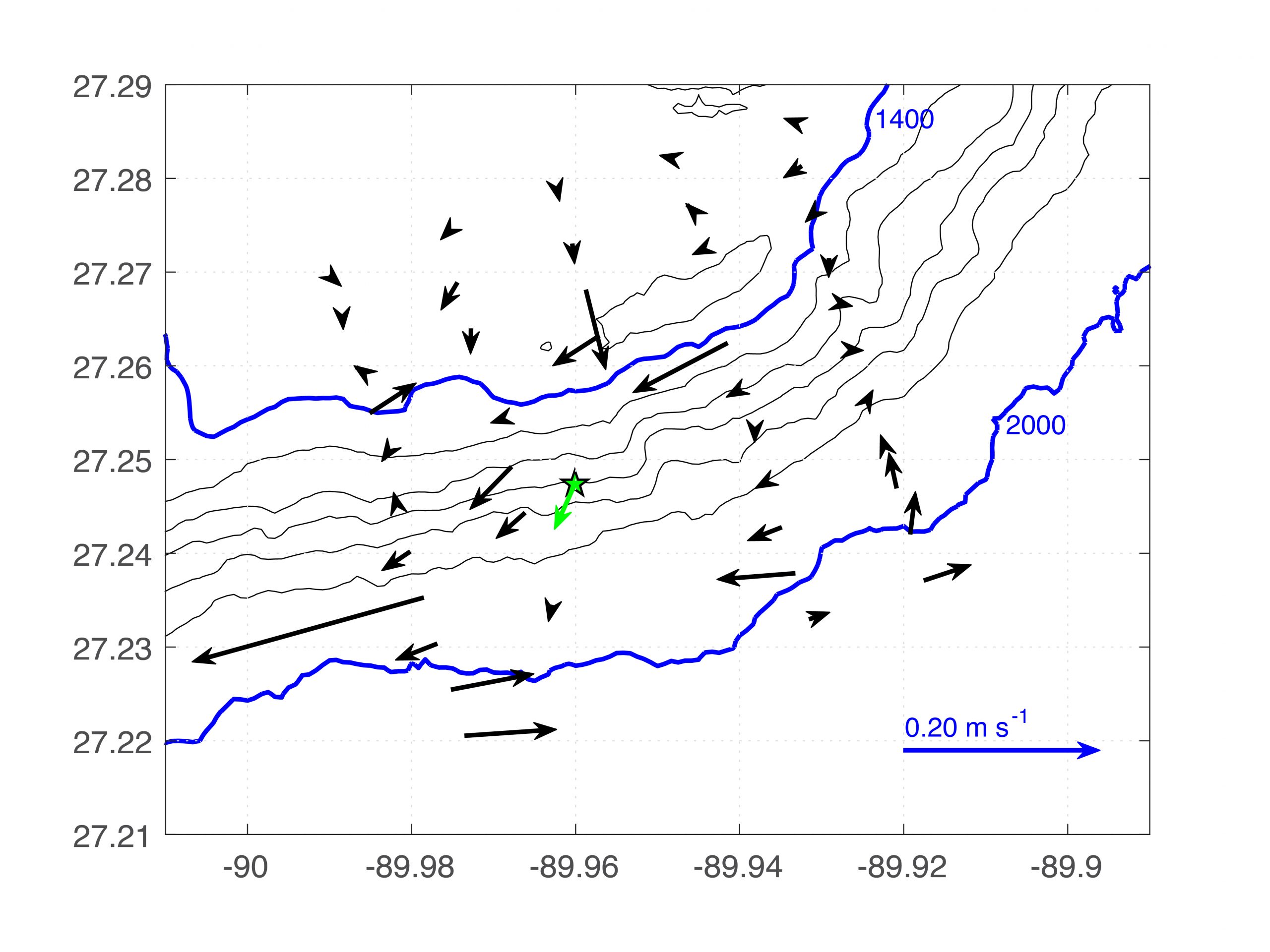

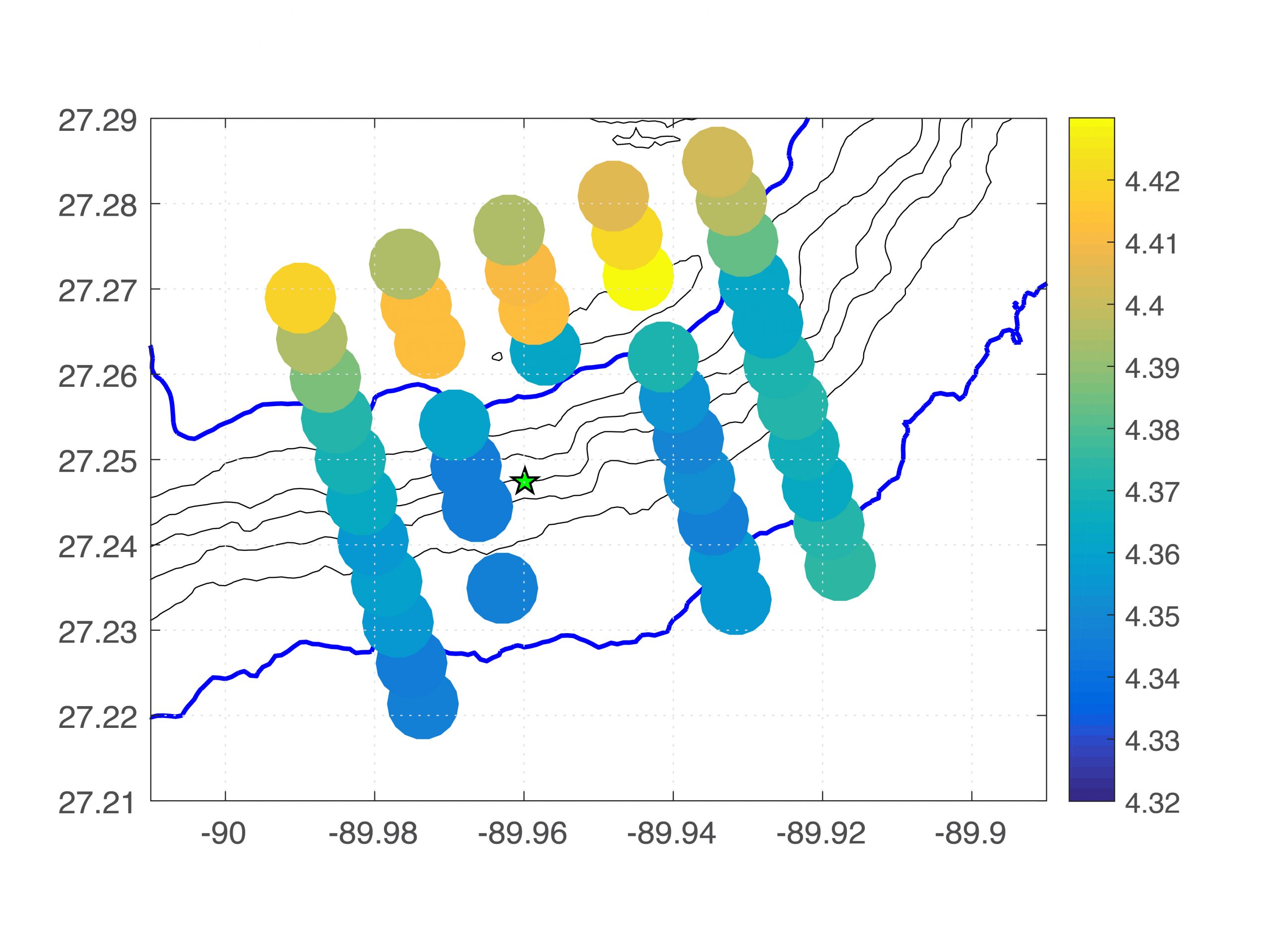

Figures 5a-c: Two-hour averages of (upper-left) TCM velocity;(upper-right) MAVS horizontal velocity; (lower left) TCM temperature centered at July 26, 21:00. The TCM array and MAVS mooring document weak flow on the slope with increasing eastward near bottom velocity at depths greater than 2000 m. Compare with the geostrophic velocity section in Figure 2. The MAVS mooring is located as the green pentagram within the TCM array.

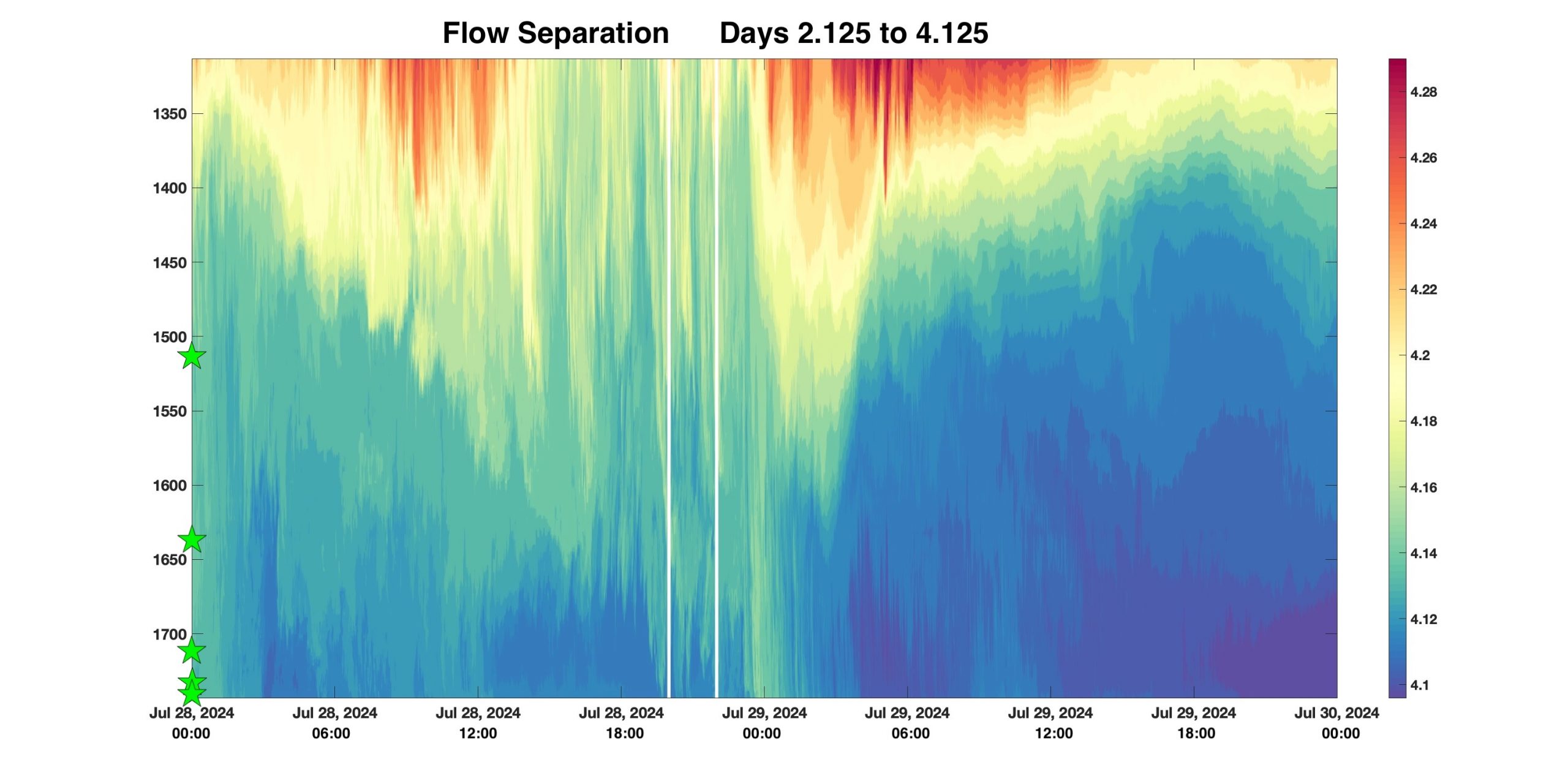

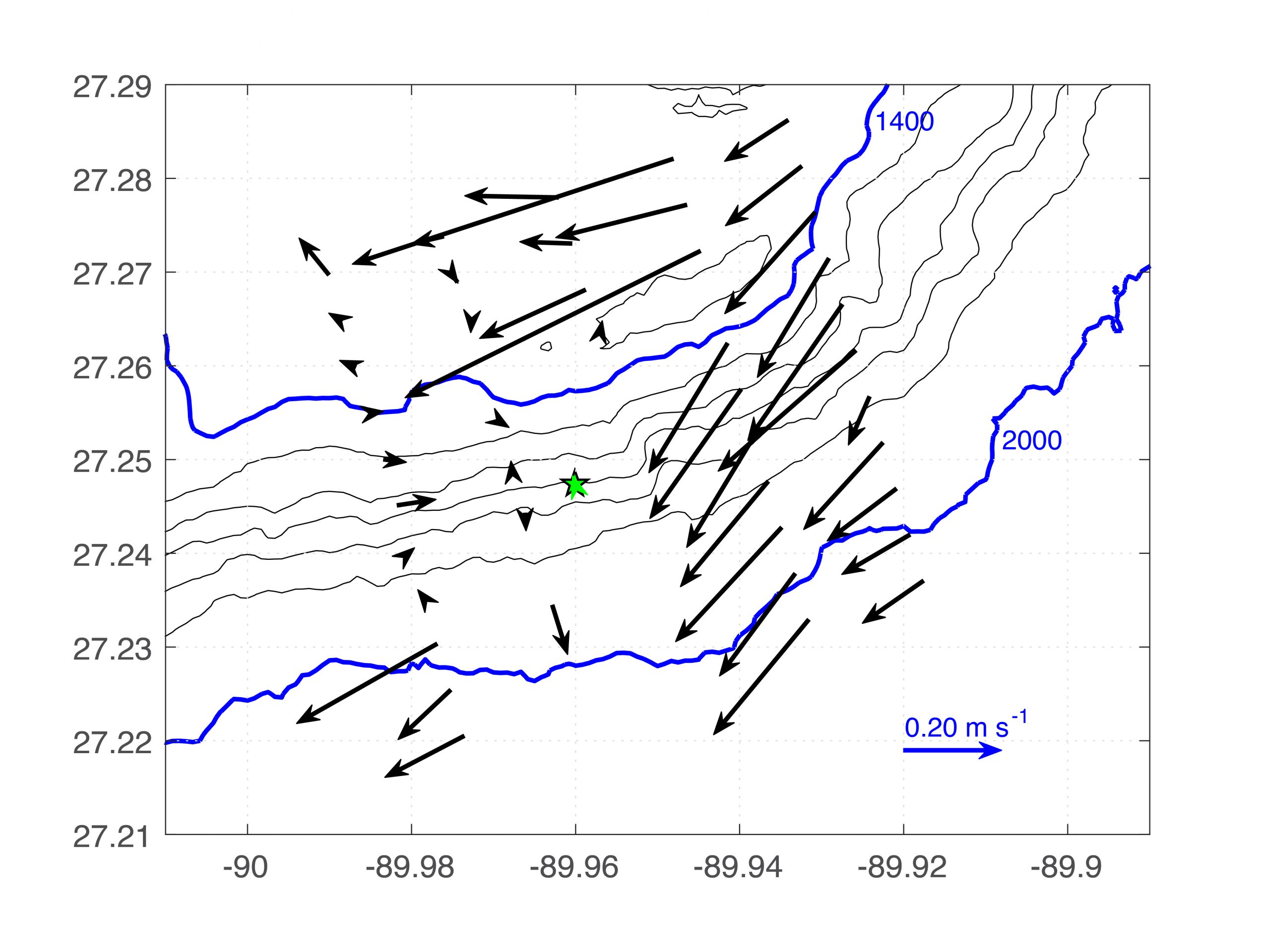

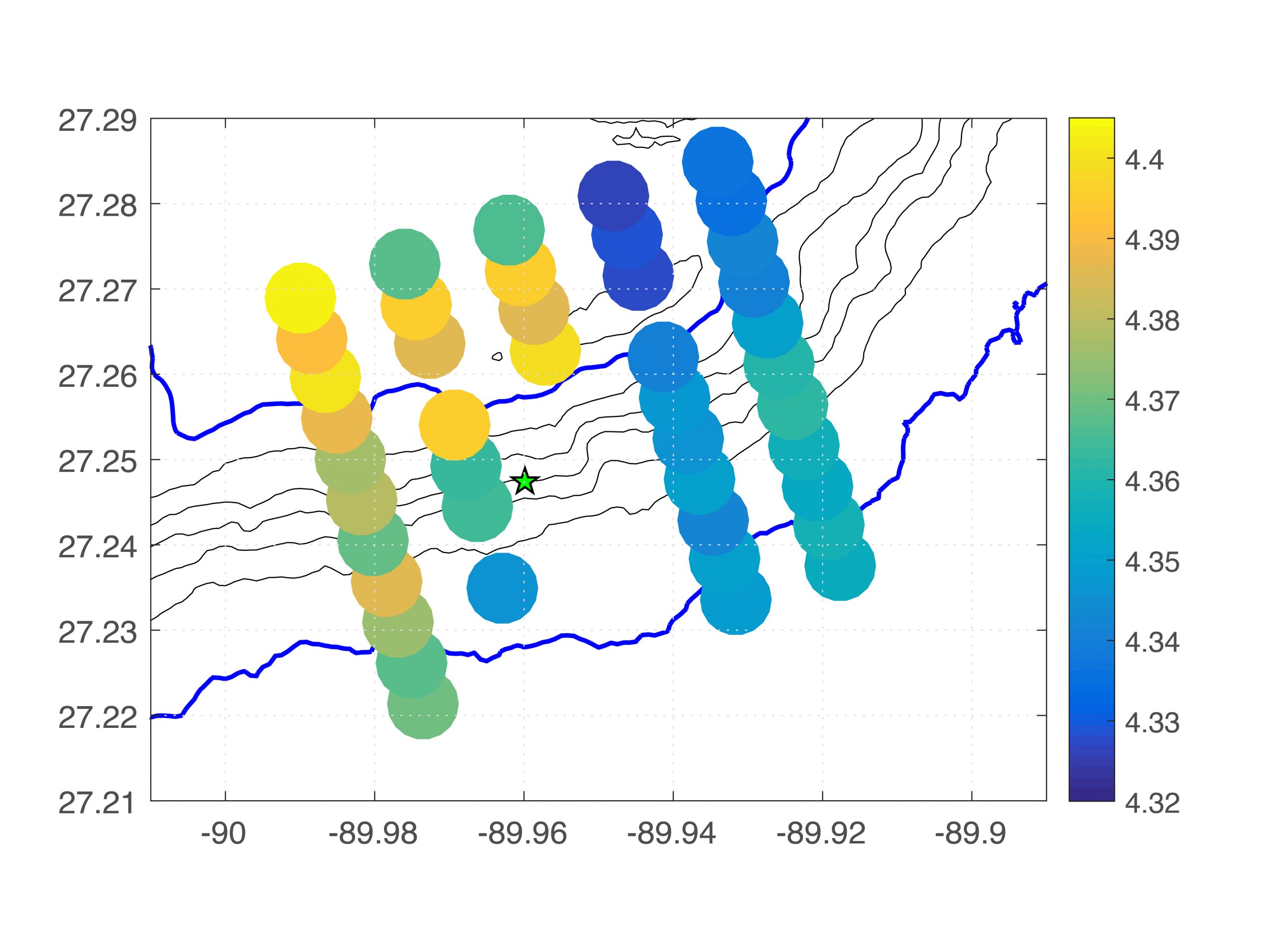

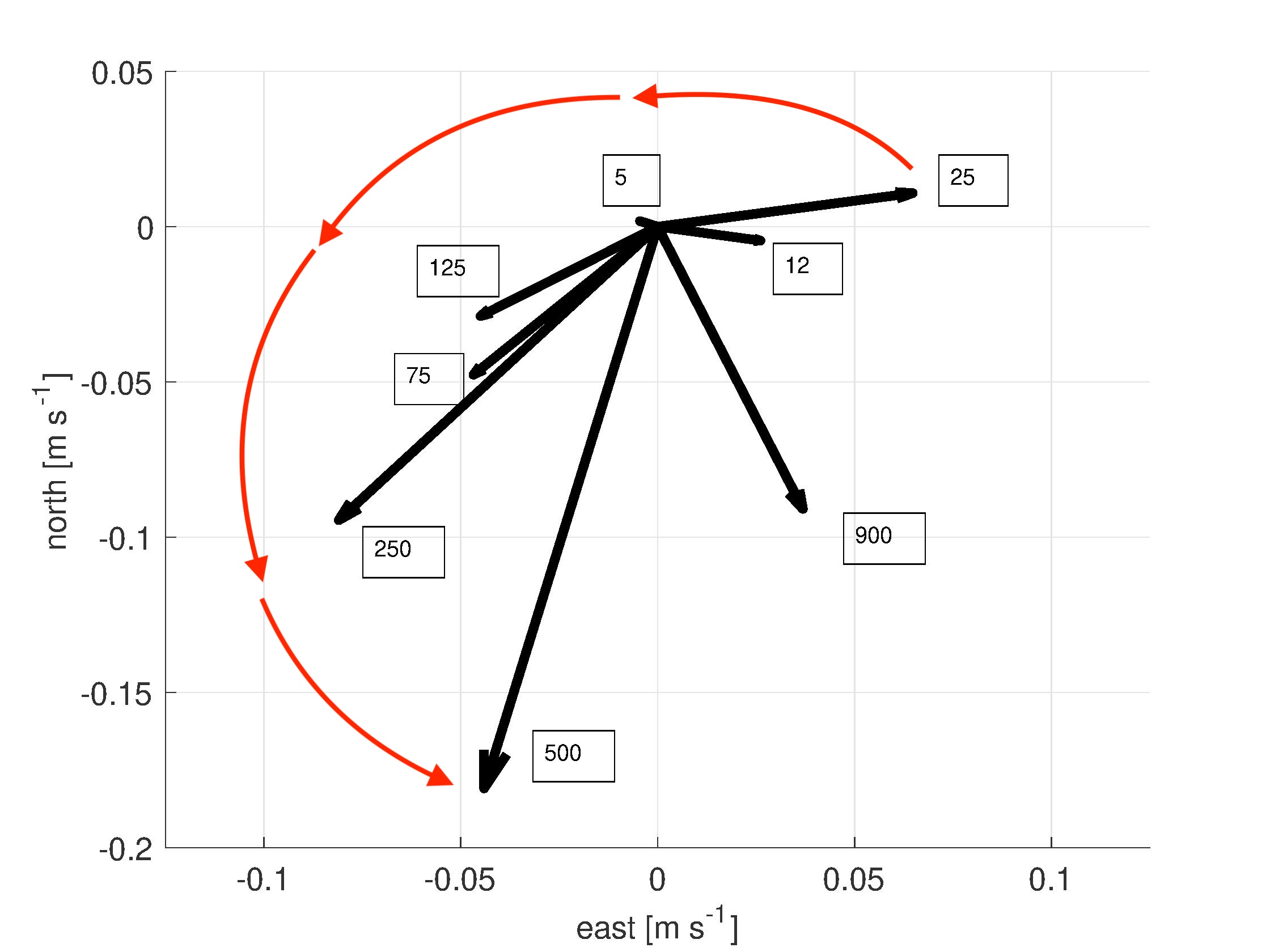

Days 2 to 4

- In the following two days, flow is noted north to south off the escarpment over ½ the network

Figure 6: DSN-Pilot. Time series of temperature recorder data for days 2.125-4.125 of the mooring deployment. The time series has a distinctly different character than that of the prior two days, Figure 4. Other DSN assets, Figure 7, document flow off the escarpment and present a possible interpretation of flow separation and vortex generation through line-stretching. Green pentagrams depict the locations of MAVS current meters. The white lines delimit the duration of time averages presented in Figure 7.

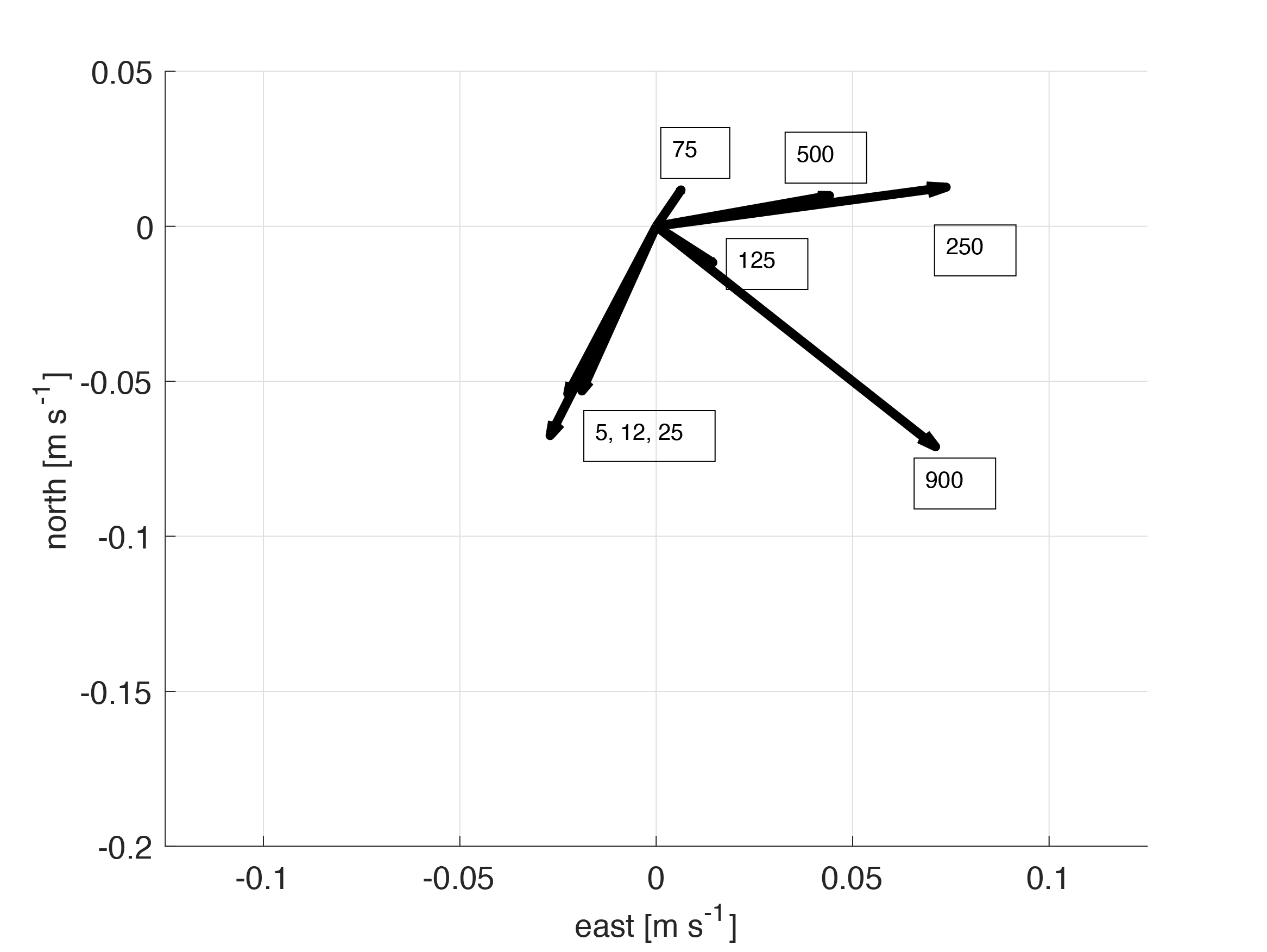

Figure 7a-c: Two-hour averages of (upper-left) TCM velocity;(upper-right) MAVS horizontal velocity; (lower left) TCM temperature centered at July 28, 21:00. The TCM array and MAVS mooring document cold dense water east and at the plateau top, flowing to the southeast over descending topography. The MAVS mooring is located as the green pentagram within the TCM array. The vertical profile of horizontal velocity rotates counterclockwise with Hab. We parse the July 28, 1400:2200 event in Figure 6 as the result of flow separation.

Days 1-111

- Time series of high-resolution temperature data from the sensor network presented in Figure 1 above. (Click here or the picture below to view movie.)