One’s work

One’s work is a way of keeping a diary. Pablo Picasso

This is very likely my last Antarctic research voyage. So, in addition to using this blog to communicate what I’m doing, I’m aiming to create a ‘diary’ that contains written and visual interpretation of the science and the environment that I’m working in. The students in my friend Mrs. Jane Baker’s Falmouth High School Art class will be participating as part of their coursework (thank you!), but anyone else is welcome to contribute to the project (thanks to Michelle Shero, Ann Tarrant and Beth Tarrant for already saying yes!). Create an artistic illustration/interpretation based on something in a post that interests you – it can be one of the images, or an aspect of the science that I’m doing, or something related to (or contrasting?) the Antarctic environment – and send me a picture of what you’ve made (rgast@whoi.edu – it needs to be <8Mb). I’ll try to include several illustrations in each blog (loaded sometime after the original post), but I intend to compile all of them into a digital document that will be available to anyone who wants a copy.

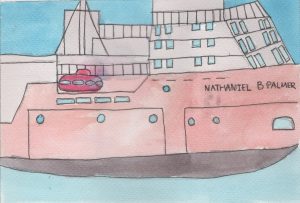

This is me on the back deck of the Nathaniel B Palmer (NBP) near Anvers Island on May 26, 2022. Ann T. brought me the hat from Rothera Station back in 2019. Not only is it Antarctic station ‘swag’, but it’s also warm and comfortable!

By E Wilson

By K Gonsalves

This is my sixth cruise since 1999, and in the spirit of my work being a diary of sorts, I’m going to briefly look back at the projects I’ve worked on in each of my posts. My first trip was as part of a LExEn grant (Life in Extreme Environments NSF) to apply DNA-based methods to study the diversity and distribution of algae and protists (microscopic single celled eukaryotes). The lead research team on the ship (the NBP, of course) was studying sea ice, and the cruise was spent doing three transects through the pack ice in the Ross Sea. It was probably the best introduction to the Antarctic marine environment that any new researcher could get. We learned how to work in the Antarctic environment. Coring ice, identifying ice ridges where slush might occur, how the ship follows leads through the ice, how it actually breaks ice, and how to sample while wearing mittens. In addition to sampling the water, we were able to collect and study the ice and the slush (that occurred at the interface of the snow and seaice). All of these environments supported a diverse, abundant and active community of microorganisms – at temperatures that were barely above freezing. The ability of biology to adapt in order to not just survive, but thrive under the extreme conditions of the Antarctic is really quite amazing.

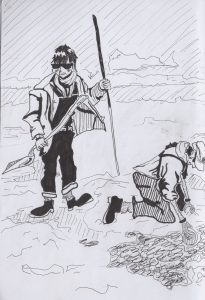

By C Rapoza

Ice coring 1999 – note how long the core extension is, suggesting an ice thickness of close to several meters.

By E Allen

But back to what we are doing here now….we are studying mixotrophy (if you read my blog back in 2019, this is going to be a bit of a repeat). Traditionally, microscopic algae and protists are considered either phototrophic (use sunlight to grow) or heterotrophic (eat prey to grow). Mixotrophy refers to a microorganism’s ability to utilize a combination of these trophic strategies. We are specifically interested in the micro-algae that eat prey. They are not unique to the Antarctic, but this alternative nutritional strategy may help them survive several months of darkness in the polar winter. There is also growing interest in understanding the role that these organisms play in the transfer of nutrients through the food web. Algae serve as the “grass” of the ocean, but not all algae are equal in terms of their nutritional quality – kind of like iceberg lettuce versus kale.

By K Shanahan

By C Champani

The reason we are studying mixotrophs in Antarctica is to understand what species are actually using this strategy, how their abundances change in different seasons, what conditions stimulate their grazing activity, and how much they contribute to photosynthesis versus how much they eat. Different mixotrophs are triggered to graze by different environmental conditions, and they will eat different amounts. They will also differ in the amount that they rely on photosynthesis versus grazing. Ultimately this means that their nutritional quality is likely different from “regular” algae, and perhaps better (or worse) for organisms higher in the food web. I’ll go into more about how we study them in later posts, but for now, meet the Sanders NBP2205 team.

By D Peters

Left to right, front row Jay-Diii (dressed for crossing the Drake), Leila, Becky (me), Bob.

Left to right, back row Chris, Liz.