Adventures in Nikumaroro

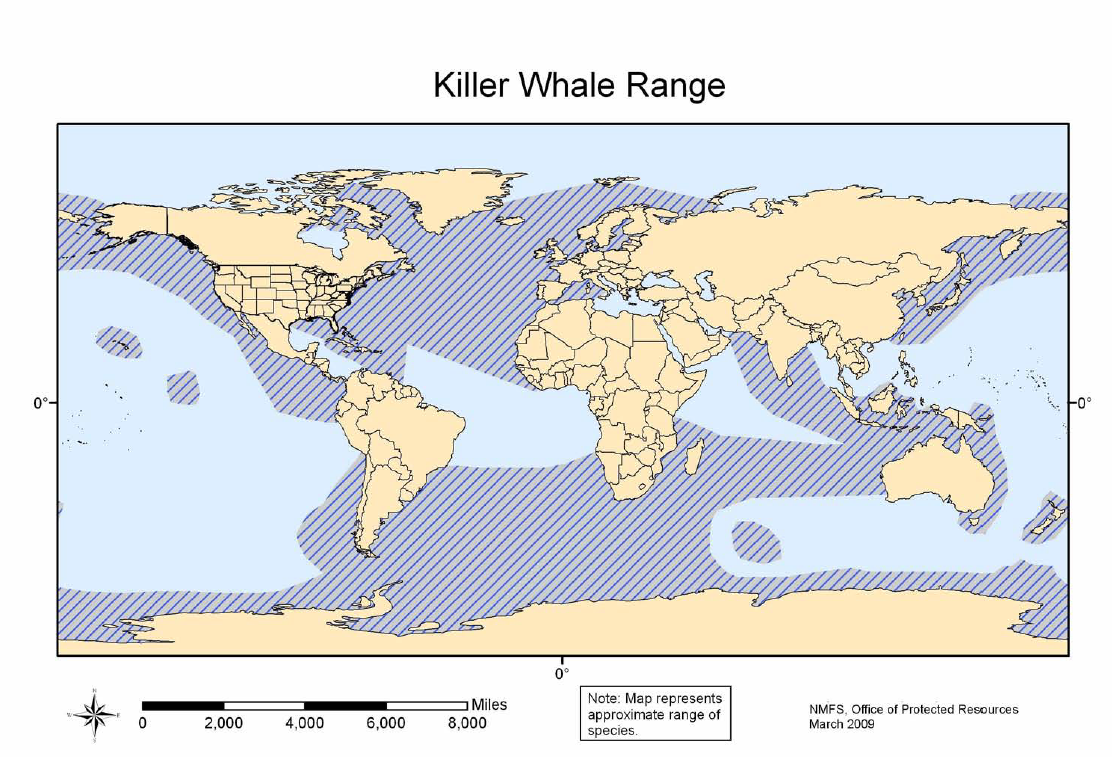

This adult orca and its calf (not pictured) represent only the second sighting of orcas, and the first of mother and calf, in PIPA, indicating that these may not be random encounters or pass-throughs by wayward animals, but that the waters around the Phoenix Islands are part of the species’ global range. (Photo courtesy of the Cohen Lab, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Pat Lohmann extracts a segment from the pneumatic underwater drill being used to extract coral cores.

Yesterday we arrived at Nikumaroro, perhaps the most famous of the Phoenix islands, as it is the supposed final resting place of Amelia Earhart.

The island came into view at dawn, shrouded in clouds on our first overcast day of the trip. Nikumaroro has much more vegetation than Kanton despite being a smaller atoll—coconut palms and Pisonea form a dense jungle all over the island. We will only have two short days to work here, before we must move on, so we hit the water swimming.

Our main objective here is to reconstruct a history of bleaching on the reef. To do this, we need to collect coral cores from massive, long-lived Porites colonies that have recorded past thermal stress events in their skeleton. But first we need to find them.

On our first work day Pat, Richard, and Mike conducted surveys across the west side of the island and, while doing so, searched for an area of reef that has enough Porites for us to core while I take water samples to understand the reef chemistry. They found a site just off the northwest corner of the island that is suitable, but may be challenging, as the weather has picked up producing a moderate swell.

Today we plan to spend the entire day coring. The corals are deeper than previous locations, which means we will be using our air rapidly and will have to make multiple dives. The swell has not diminished and so we decide to tie extra ropes to nearby reef rocks to give Pat, our driller, extra handholds. This will allow him to drill a straight hole, which is critical to getting the long records we are after. After a quick breakfast, we head out in both tenders: one full of divers, the other full of extra air tanks.

The drilling setup is elegant in its simplicity; we use a pneumatic drill that has been outfitted to connect to a scuba regulator, which we attach to a full scuba tank. The bit is a 3.5-centimeter-diameter concrete coring bit, which we have repurposed for coral. When Pat pulls the trigger, air from the tank spins the drill and drives the bit into the coral skeleton. We break off sections of core at 30-centimeter intervals, after which we insert aluminum extensions into the drill shaft to extend the bit deeper into the colony. Once the core is completely out, we patch the coral colony with carbonate rubble and epoxy to provide a surface for new coral polyps to grow, a process that typically takes less than a year.

Over three hour-long dives we collect 10 cores, the longest of which is over 100 centimeters and records about a century of growth. We also take tissue samples to analyze for genetics and feeding habits.

Over the course of the day we were visited by an abundance of reef wildlife including a school of barracuda, several black tipped reef sharks, some overly inquisitive red snapper. At the end of the day while Mike and Eric conducted a plankton tow and they encountered two orcas—an adult and a juvenile. The adult, over 20-feet long, makes them feel very small in their 9-foot tender.

Tomorrow we will land on the island so that our observer, Burangke, can make his assessments of the vegetation and wildlife.

The current map showing the distribution of orcas worldwide may need to be updated to include PIPA. (NOAA Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources)