The emperor penguins are calling

Our title echoes a line from a letter by John Muir, the “Father of the National Parks,” to his sister in 1873: “The mountains are calling and I must go…”—a statement driven by deep curiosity and a sense of responsibility to protect nature. Today, scientists face a similar call to action. In a rapidly changing world, we carry the responsibility of producing knowledge that informs both national and global decisions. For Antarctica, this includes improving the odds that iconic species like the emperor penguin will persist into the next century.

The emperor penguin, now protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA), is not evolutionarily adapted to withstand rapid environmental changes. Because its survival depends heavily on sea ice, it is especially vulnerable to ongoing shifts in Antarctic conditions. The ESA—the world’s strongest law for preventing extinction—requires that listing decisions be grounded in the best available science. In support of this, an interdisciplinary team of ecologists, climate scientists, and policy experts—including our group—provided data, models, and projections to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for a comprehensive threat assessment (Jenouvrier et al. 2021).

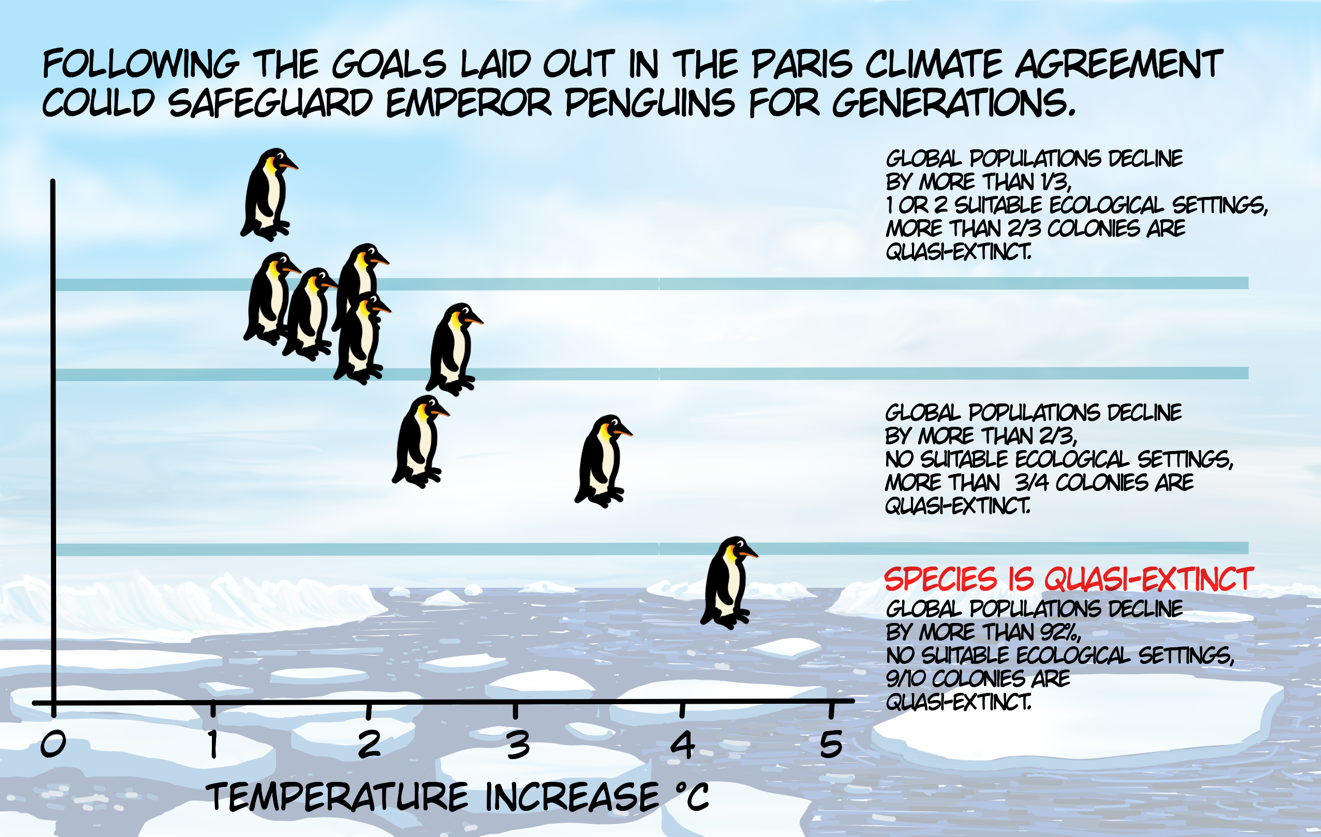

This assessment followed the “3Rs” framework—resiliency, redundancy, and representation—which evaluates whether a species can withstand, recover from, and adapt to environmental pressures. Our research showed that under current global emission trends, emperor penguin colonies would face widespread quasi-extinction by 2100, primarily due to projected sea ice loss. These projections were based on ecological models informed by decades of demographic data and the latest Earth system climate projections.

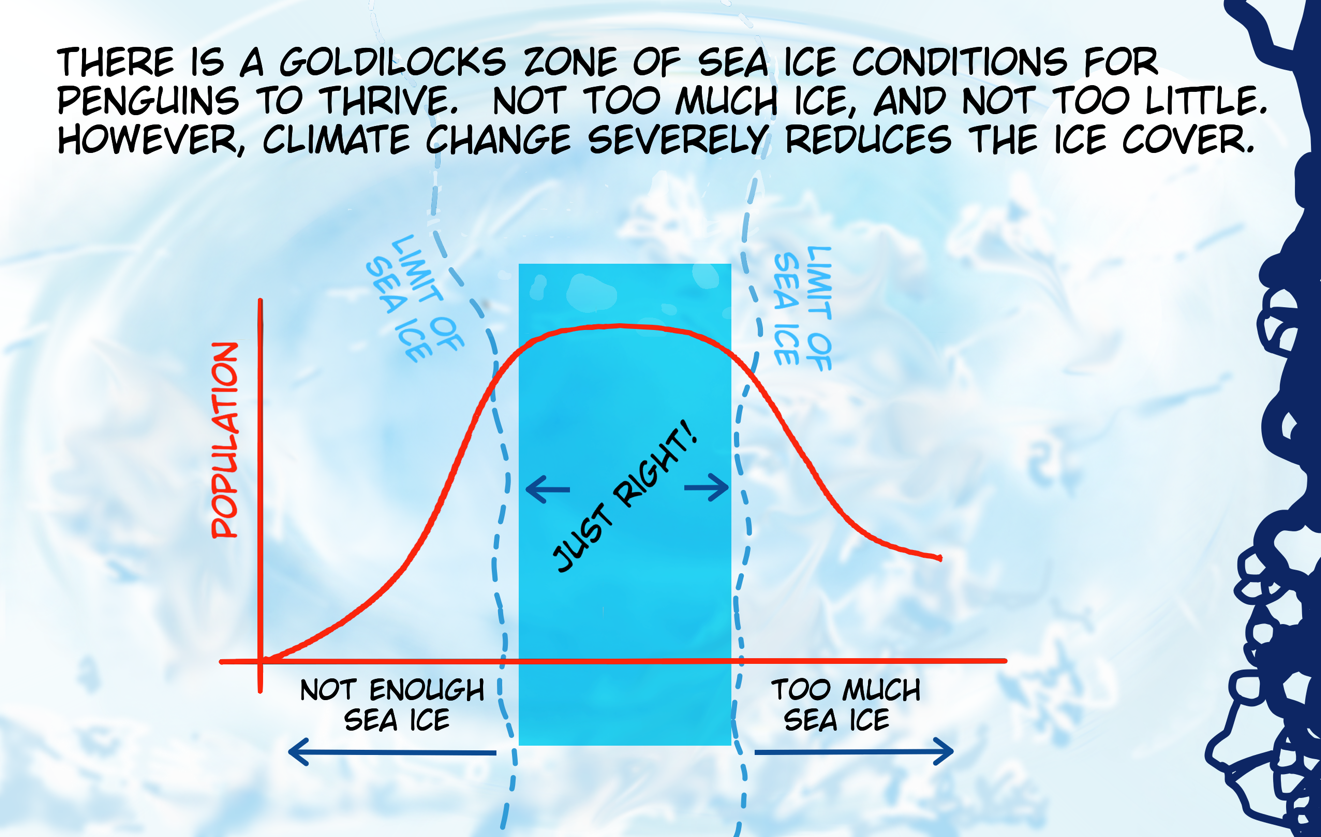

My own connection to this species began during my PhD at CNRS, when I visited the emperor penguin colony at Pointe Géologie—made famous by March of the Penguins. I still remember the moment a curious penguin gently tugged at my shoelaces, its sleek plumage glinting in the sun. Our studies revealed a clear “Goldilocks zone” for sea ice: too little, and chicks drown when ice breaks up early; too much, and adults struggle to feed, risking starvation for themselves and their young (Jenouvrier et al. 2012).

To understand what lies ahead, I moved to the U.S. to work with demographer Hal Caswell and sea ice experts Marika Holland and Julienne Stroeve. Together, we linked demographic models to climate projections and showed that not just Pointe Géologie, but nearly all colonies would be at risk if environmental changes continue unchecked (Jenouvrier et al. 2014).

Still, I hoped that emperor penguins might adapt—by shifting breeding grounds, for instance. Collaborating with mathematician Jimmy Garnier, we developed a metapopulation model that tested different dispersal and habitat-search behaviors. Sadly, none were sufficient to reverse the projected global decline (Jenouvrier et al. 2017).

With colleagues from the British Antarctic Survey and University of Minnesota, we also incorporated extreme events like early sea ice breakup into our models—events that satellite imagery now documents with increasing frequency. These analyses revealed that such events could accelerate population losses, potentially causing 98% of colonies to reach quasi-extinction and reducing global abundance by 99% by 2100 if emissions remain high (Jenouvrier et al 2021).

But there is hope. In one of our most policy-relevant studies, we examined what would happen if the world met the Paris Agreement targets (Jenouvrier et al 2020). Using specially designed climate simulations, we found that strong mitigation would preserve climate refuges and halt the projected decline. I remember rushing to share these results with Marika: “We can do it—penguins can persist if we meet the Paris goals!”

Yet, whether these goals are met remains uncertain. While global pledges have moved in a positive direction, current pathways still point to warming above 2°C. As such, the emperor penguin has become a symbol—much like the proverbial “canary in the coal mine”—for the far-reaching consequences of decisions made today.

Penguins live in balance with one of Earth’s most extreme environments. Their vulnerability makes them powerful indicators of broader environmental change. Listening to their call means listening to what science tells us—about risk, about resilience, and about the urgent need for informed action.

Current and Past Grants Supporting Our Emperor Penguin Research

- Morss Institute Colloquia Award: Conservation of Polar Species Endangered by Climate Change

- NSF: Collaborative Research: Polynyas in Coastal Antarctica (PICA): Linking Physical Dynamics to Biological Variability

- NSF: Collaborative Research: A multi-scale approach to understanding spatial and population variability in emperor penguins

- NSF: Collaborative Research: Integrating Antarctic Environmental and Biological Predictability to Obtain Optimal Forecasts

- NASA: Antarctic Marine Predators in a Dynamic Climate

- NASA: Hot Spots in the Ice: Revealing the Importance of Polynyas for Sustaining Antarctic Marine Ecosystems

Related Links

- Articles by Stephanie Jenouvier - The Conversation

- Emperor Penguins on Thin Sea Ice - Frontier

- Emperor Penguins in a Changing World: Unveiling Current Trends and Predicting Future Scenarios - Antarctic Environments Portal

- Emperor Penguin Gets Endangered Species Act Protections - U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service