Dispatch 12: Chasing Ice

Isabela Le Bras

September 2, 2021

Along the northern stretch of our cruise track, our plan was to deploy four ice-based observatories. These included 4 Ice Tethered Profilers (ITPs), 3 Tethered Ocean Profilers (TOPs), 2 Seasonal Ice Mass Balance Buoys (SIMBs), and 1 Arctic Ocean Flux Buoy (AOFB). ITPs measure ocean salinity and temperature along an 800m wire hanging below the sea ice. Two of the ITPs aboard also included oxygen sensors and stationary Submersible Autonomous Moored Instruments for partial pressure of CO2 (SAMI-CO2). TOP is a new profiler designed to bump into the sea ice and measure the near-ice water properties, which the ITP does not measure. SIMBs measure ice and snow thickness, and AOFBs measure under-ice heat and momentum fluxes as well as atmospheric properties. Co-locating multiple platforms allows us to cross-calibrate them and to better understand the full air-ocean-ice system.

The challenge before us was to find four suitable locations for these platforms. For each station, we needed to find a floe large enough to park the Louis in and walk on safely, with roughly 1m thickness, and as few ridge features as possible. We wanted to space the stations about 100km apart to get good coverage of the area. Since setting up these systems takes many hours, ideally, we would find a spot every morning before breakfast.

Things didn’t look too promising on September 1st in the northwest corner of our clockwise cruise track. The sea ice was sparse and every floe we encountered crumbled beneath the Louis. By lunchtime, we still had not found anything and decided to do an open water ITP deployment to ensure appropriate spacing. Of course, we could not co-locate any other platforms using this method. Our hope was that this ITP would freeze in soon as they have successfully in the past.

September 2nd got off to a more auspicious start. First mate Nick Houle pulled into a potential floe at about 6:30 in the morning and Jeff O’Brien and Cory Beatty completed a sea ice survey before breakfast. They were lowered over the side onto the sea ice and Jeff tested the ice with a pick before stepping onto it. Cory followed in his footsteps and together they drilled through the ice and measured its thickness, reporting back over radio. The first message was “Seven-Five centimeters”. Not quite one meter, but thick enough to proceed with the survey. Luckily, the sea ice at the next locations was a little thicker, 80, then 95, then 85cm. Because we were aiming to recover a nearby ITP that same day, and the sea ice was likely to be thicker to the east, it was decided that this ice-based observatory would include three out of the possible four components: an ITP, a SIMB, and a TOP.

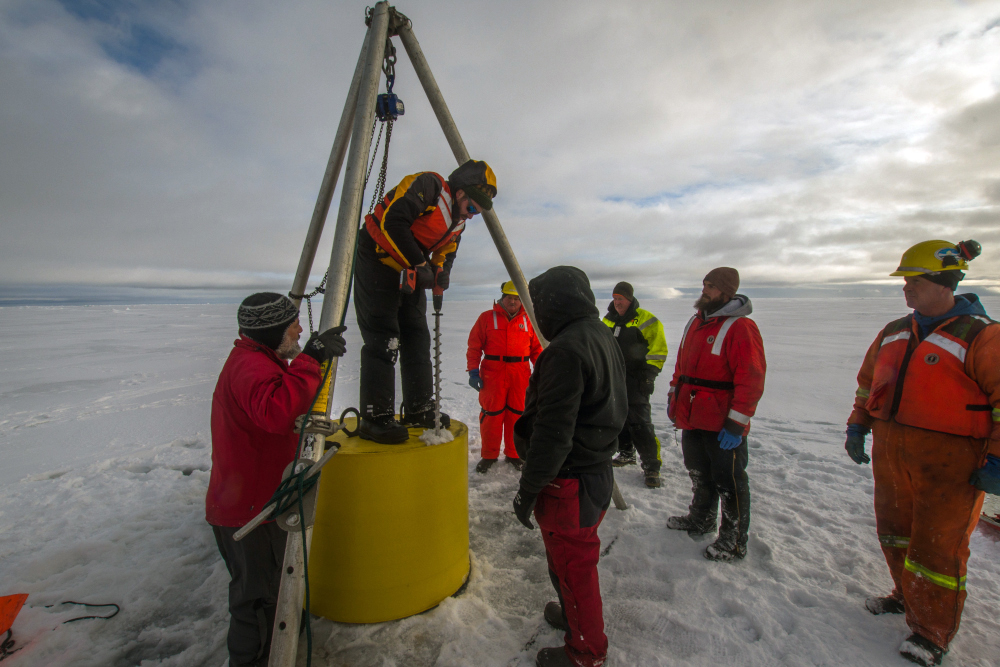

After breakfast the deck crew lowered the gangway and craned over instruments and tools directly onto the sea ice. Five hours, several snow flurries, and a lot of hauling, shoveling, drilling, winching, tying, and final computer-checks later, the station was complete. The day was not over yet, though! We still had an ITP that had ceased functioning to pick up.

Last year, ITP 119 had been too far west to recover, but had drifted back over the Northwind Ridge into the JOIS 2021 area. The Louis was receiving hourly ITP 119 position updates and was able to track it down and dislodge it out of the small floe it was found in by first ramming the floe with the bow and then sending the starboard bubblers at it. Once dislodged, the ITP shot along the Louis and seemed to have a mind of its own, evading Roger Carew, who managed to hook onto it from the hanging (hu)man basket. Another hour later, the muddy ITP119 was aboard and the Louis headed east in search of the next ice floe, filled with tired but happy passengers.