Dispatch 9: Field Trip to the Engine Room(s)

Helen Gemmrich

August 30, 2021

If the Louis were a small town, the engine room crew would be its entire public works department. In addition to keeping the ship’s engines and mechanical components running smoothly, the team of 18 engineers, oilers, technicians and electricians also handle the ship’s heating, refrigeration, electricity, water treatment and waste management. If you ask nicely, they sometimes even take curious scientists on a tour through the ship’s engine rooms!

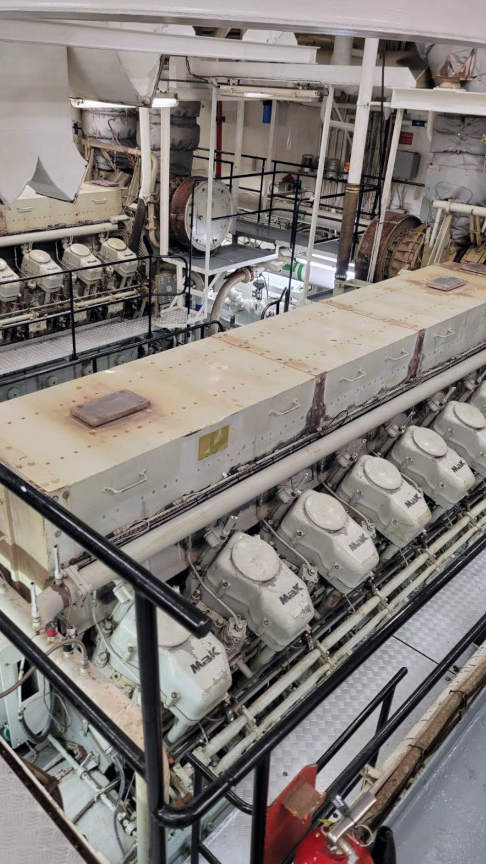

For a tourist from the upper decks, the engine room is overwhelming. Within minutes, I completely lost any sense of orientation. All I saw was mechanical chaos. Pipes climb the walls like vines, dotted with brightly coloured valves and feeding into tall structures dominating the room. Large metal cases housing motors and generators share the space with workshops and water tanks. Watertight doors, steep stairs, overhead gangways and deck hatches lead to other parts of the ship. There are no windows, but at all times, you hear and feel the engines turning. It is loud, labyrinthine, and very, very impressive.

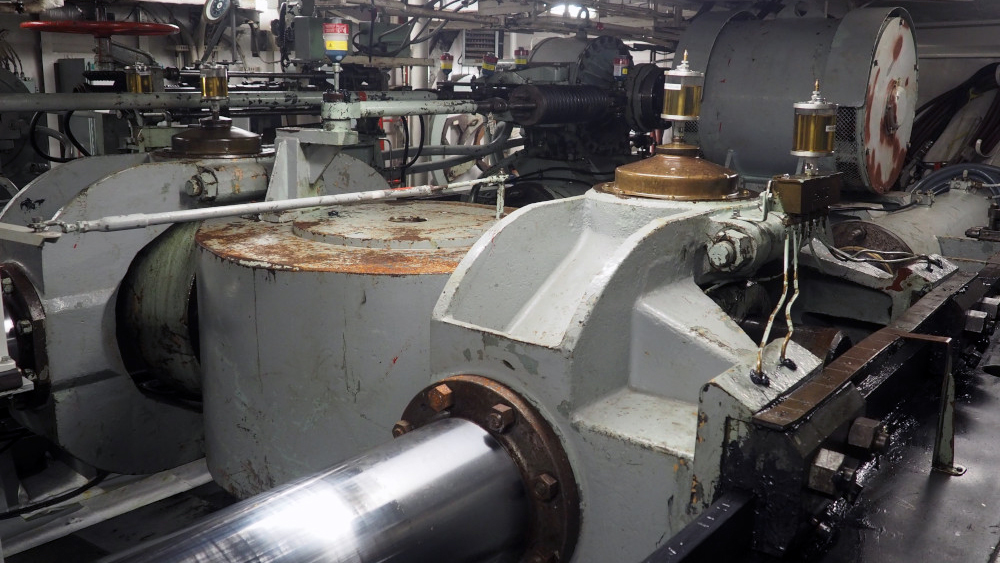

As we wove our way through the different areas, Tour Guide/Senior Engineer Stu Maclean pointed out fun facts (for example, that valves are color coded: red for fire and emergency equipment, yellow for oil, blue for water, purple for steam) and safety features (like submersible pumps that can be controlled from the upper decks in case of flooding). We ducked into the “limbo room,” where pipes of many sizes crisscross along the room at eye level, and stopped under the cavernous chimneystack that grows from the lower decks to high above the bridge. Standing next to the massive steering gear and engine shafts was a striking reminder of just how big and powerful the Louis is. There are pistons the size of dinner plates and wrenches longer than my arm.

The Louis has five main engines, although regular operations usually require only two or three. Diesel engines power electric motors, which drive three propeller shafts and ultimately move the ship. At full capacity, the ship carries roughly 3,500 “cubes” (3.5 million litres) of fuel spread across 26 tanks, and can reach a maximum speed of 22 knots for search and rescue operations.

Our last stop on the tour was the engine control room: a long rectangular room filled with dials, buttons, gauges and logbooks. Engineering drawings cover the tall control panel cabinets lining both sides of the central console. From here, the engine team keeps an eye on the ship’s systems, logging routine maintenance, inspections and the occasional troubleshooting.

Then, suddenly, we walked through an unremarkable door and were back in the main deck corridor. The deafening noise died down to a background hum as we returned to our daily tasks – this time with a small glimpse at the inner workings of another world at sea.