Dispatch 6: Did you know that ice has a birthday?

Helen Gemmrich

August 26, 2021

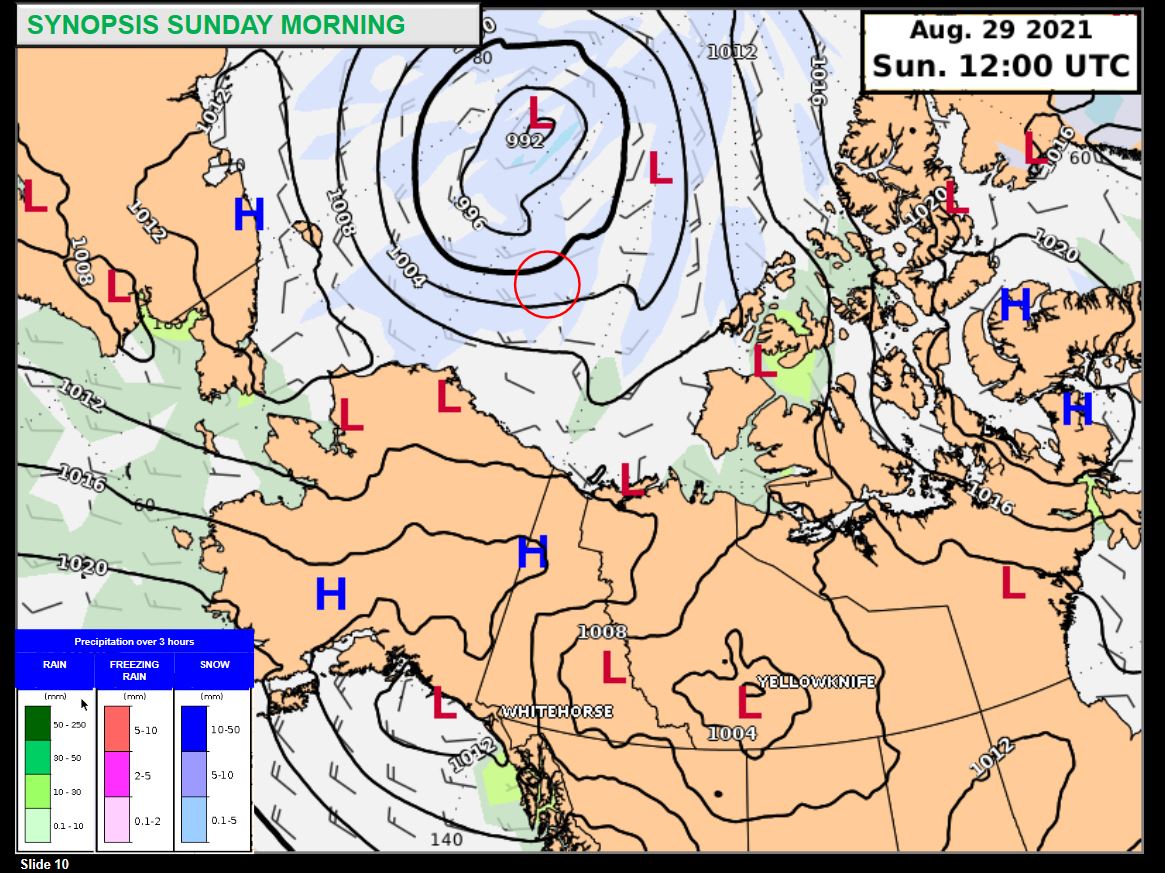

At 5:30 a.m. every morning, Francis Beaulieu rolls out of bed and fires up the ice forecast computers on the bridge deck. A weather and ice forecast must be ready by 7 a.m. for the Captain’s briefing.

“It doesn’t actually take that long to prepare the briefing, but that’s how long it takes to get the files from the server,” he said, laughing. The ship’s satellite internet connection can be quite slow, occasionally cutting out completely when we head north. Loading a webpage can take a few minutes, downloading even longer.

Francis is an Ice Service Specialist with the Canadian Ice Service (CIS), which provides daily ice forecasts for Canadian waters. Knowing what kind of ice (and how much) lies ahead helps the navigation officers choose areas that avoid wear and tear on the ship and optimize time and fuel consumption. Breaking through ice feels a bit like airplane turbulence, so choosing the nicest route is not only the safest option, it is also greatly appreciated by the crew!

Using the ice service’s weather and ice models, satellite imagery, ice charts and direct observation (sometimes from the helicopter!) Francis looks at the conditions for the next 48 hours, up to the next five days. Throughout the day, he observes the ice, sea state and weather conditions, logging everything from ice type and quantity to waves, wind, and clouds. In addition to keeping the navigation officers up to date on any upcoming hazards, his reports provide real time feedback for the ice service’s models.

“There’s a lot to take into consideration, like the thickness of the ice (…) and the stage of development,” he said.

The ice in our research area is mostly sea ice: salty, frozen ocean water. Not to be confused with icebergs! Whereas sea ice comes from the ocean, icebergs are freshwater chunks that broke off glaciers on land. Ninety percent of an iceberg is underwater, which – as we know from the Titanic – can be incredibly dangerous to ships. (Fun fact: small icebergs are called “bergy bits.”) There are no icebergs here, but we do get to see some very big sea ice!

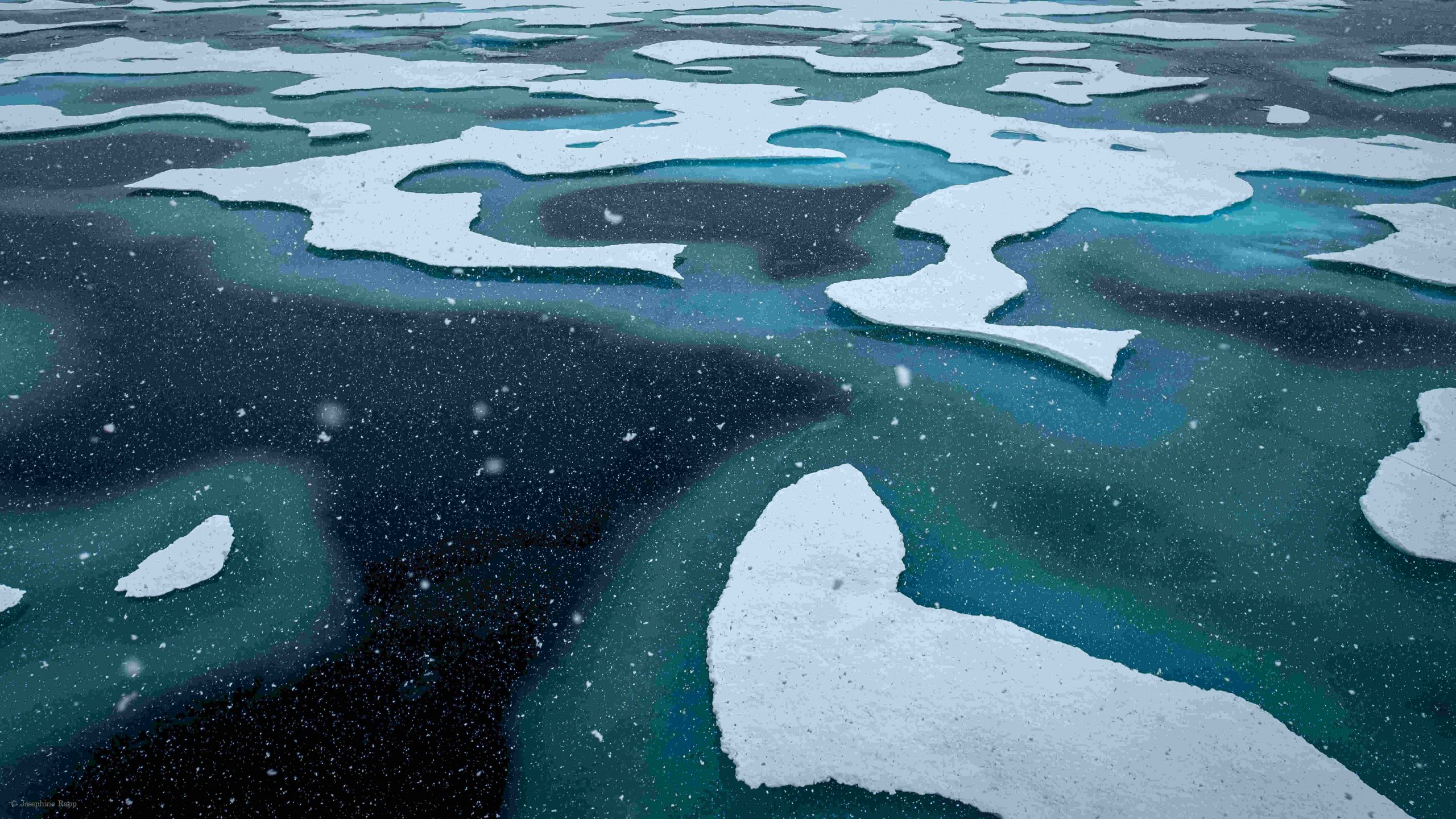

In the summer, the sea ice melts and creates ponds of fresher water on top of the ice floe. Ice that survives the summer officially turns “old” on Oct. 1. “Happy birthday to the ice!” Francis said.

Even at the same thickness, old ice is much more dangerous than first-year ice since it is harder to break, he added. Part of his job is to identify old ice on his ice charts for the captain. The most common signs of old ice are a distinct, Caribbean blue tinge and a more worn surface. In comparison, thick, first year ice has sharp edges and ridges. In the right conditions, sea ice grows one meter thicker per year!

With our reversed science plan this year, we will reach concentrated old ice patches in a few weeks.