Dispatch 7: Recovery and Redeployment

Helen Gemmrich

August 28, 2021

This year’s science plan includes recovering and redeploying three moorings in the Beaufort Sea. The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) team was unable to recover the moorings last year due to COVID-19, so the instruments waited in the water for nearly three years instead of the intended two. While the instruments on the mooring have a longer battery life than the planned timeframe (just in case!), extending the deployment by an entire year had everyone holding their breath leading up to the first mooring’s recovery.

On Friday morning, it was all hands-on deck: Boatswain Rico Amamio and Chief Mate Andrew Gidge led a crew of 13 people bundled up in fluorescent floatation suits and safety gear. They had practiced the recovery process the day before with Jim Ryder, testing the equipment and making sure all the necessary tools were close by. Constant communication between the deck, the scientists and Captain MacDonald on the bridge kept everyone on the same page, so when the recovery was underway, everyone knew where to be and what to do. From the bridge, the deck crew looked like a handful of well-organized highlighters in hardhats.

Moorings are essentially a long wire strung with scientific instruments, anchored to the bottom of the ocean by an 8,300-kilogram weight and pulled upwards by a large buoyant top float. Profilers glide along sections of the wire, collecting temperature, salinity, pressure and velocity data along the water column. Other instruments stay at a specific depth and measure everything from pressure and ice thickness to waves. The moorings create a long-term time series in a single location.

The top of the mooring is 30 meters underwater and can’t be seen from the surface. Ideally, a locator beacon on the top float signals the mooring’s location to the science team. Unfortunately, the beacon’s battery died in the three years. Instead, the Louis circled the mooring’s approximate location and the team was able to determine the location from signals received from the locator beacon at the bottom of the mooring – almost four kilometers down! The circling also helped create open water in the area, so the top float wouldn’t be stuck under the ice when it came up.

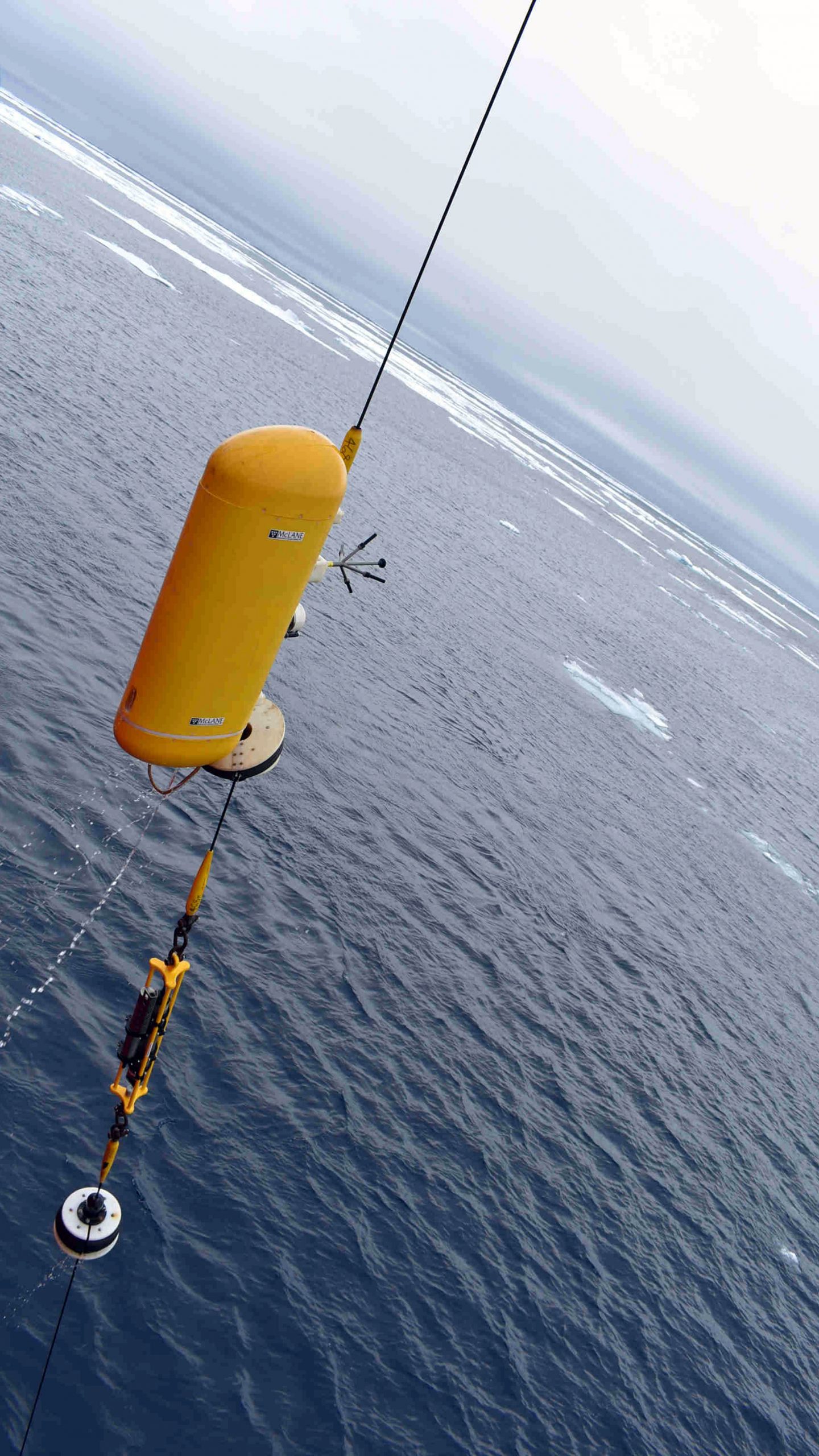

An acoustic signal released the mooring from the anchor, and the big yellow top float popped to the surface. All available personnel who were not on deck lined the bridge windows, trying to spot the yellow sphere through binoculars. Up close, the top float is just over five feet tall, but floating in the ocean it looks more like a small fluorescent marble. We did eventually spot it behind some sea ice, and the deck crew was able to hook it with the winch and bring it aboard.

Meter by meter, the foredeck winch pulled the mooring out of the ocean. The team stopped at intervals to remove instruments and transfer the mooring’s weight from the winch to the crane. Last to come up were 52 glass floatation balls. Their big yellow casings looked like a pile of giant grapes all bunched up on the foredeck.

After the recovery, the WHOI team downloaded the data from the instruments and had a first look at the mooring’s last three years. Miraculously, some instruments worked the whole time! Others stopped collecting data after roughly one year. Jeff O’Brien and Fred Marin worked late into the night, reprogramming the instruments for redeployment the next morning. The deployment works nearly exactly like the recovery, except in reverse. The full recovery took just over four hours, and the redeployment took five.

One down, two to go. Fingers crossed the mooring will have some nice data for us when we return next year!